What Is an Action Potential?

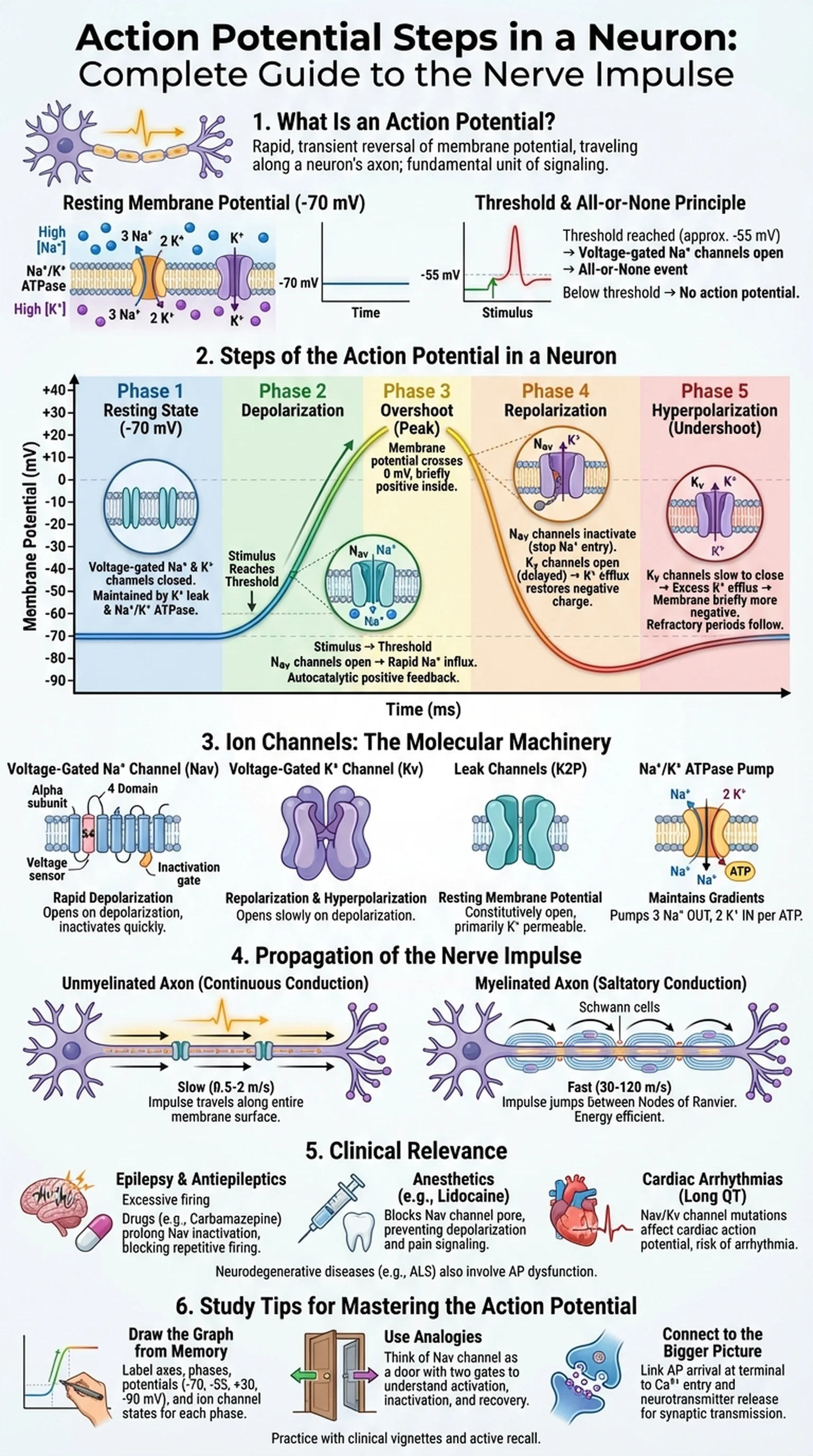

An action potential is a rapid, transient reversal of the electrical membrane potential that travels along the axon of a neuron, serving as the fundamental unit of signaling in the nervous system. Understanding the action potential is essential for students of neuroscience, physiology, and medicine, as it underlies everything from reflexes to cognition.

At rest, a typical neuron maintains a resting membrane potential of approximately -70 millivolts (mV), with the inside of the cell negatively charged relative to the outside. This resting potential is established primarily by the selective permeability of the membrane to potassium ions (K+) through leak channels and by the activity of the sodium-potassium ATPase pump (Na+/K+ ATPase), which actively transports three sodium ions (Na+) out of the cell for every two K+ ions pumped in. The resulting electrochemical gradients—high Na+ outside, high K+ inside—create the stored energy that drives the action potential.

When a stimulus depolarizes the membrane to a critical level called the threshold (typically around -55 mV), voltage-gated sodium channels open rapidly, allowing Na+ to flood into the cell. This triggers an all-or-none event: if threshold is reached, a full action potential fires; if it is not, no action potential occurs regardless of how close the stimulus came to threshold. This all-or-none principle means that the action potential does not vary in amplitude—information is encoded instead by the frequency of action potentials and the pattern of neurons firing.

The action potential is the basis of the nerve impulse, the electrical signal that propagates along axons to transmit information between neurons and from neurons to muscles and glands. Each nerve impulse follows an identical sequence of ion channel openings and closings, producing the characteristic spike seen on an oscilloscope or electrophysiology recording. Grasping the action potential steps in a neuron is therefore the gateway to understanding neural communication, synaptic transmission, and the pharmacology of drugs that target ion channels.

Key Terms

A rapid, transient reversal of membrane potential that propagates along a neuron's axon, serving as the electrical signal for neural communication.

The electrical potential difference across the neuronal membrane at rest, typically about -70 mV, maintained by ion gradients and selective permeability.

The critical level of depolarization (approximately -55 mV) that must be reached to trigger the opening of voltage-gated Na+ channels and initiate an action potential.

The concept that an action potential either fires at full amplitude when threshold is reached or does not fire at all; there is no partial response.