What Is the Cardiac Cycle?

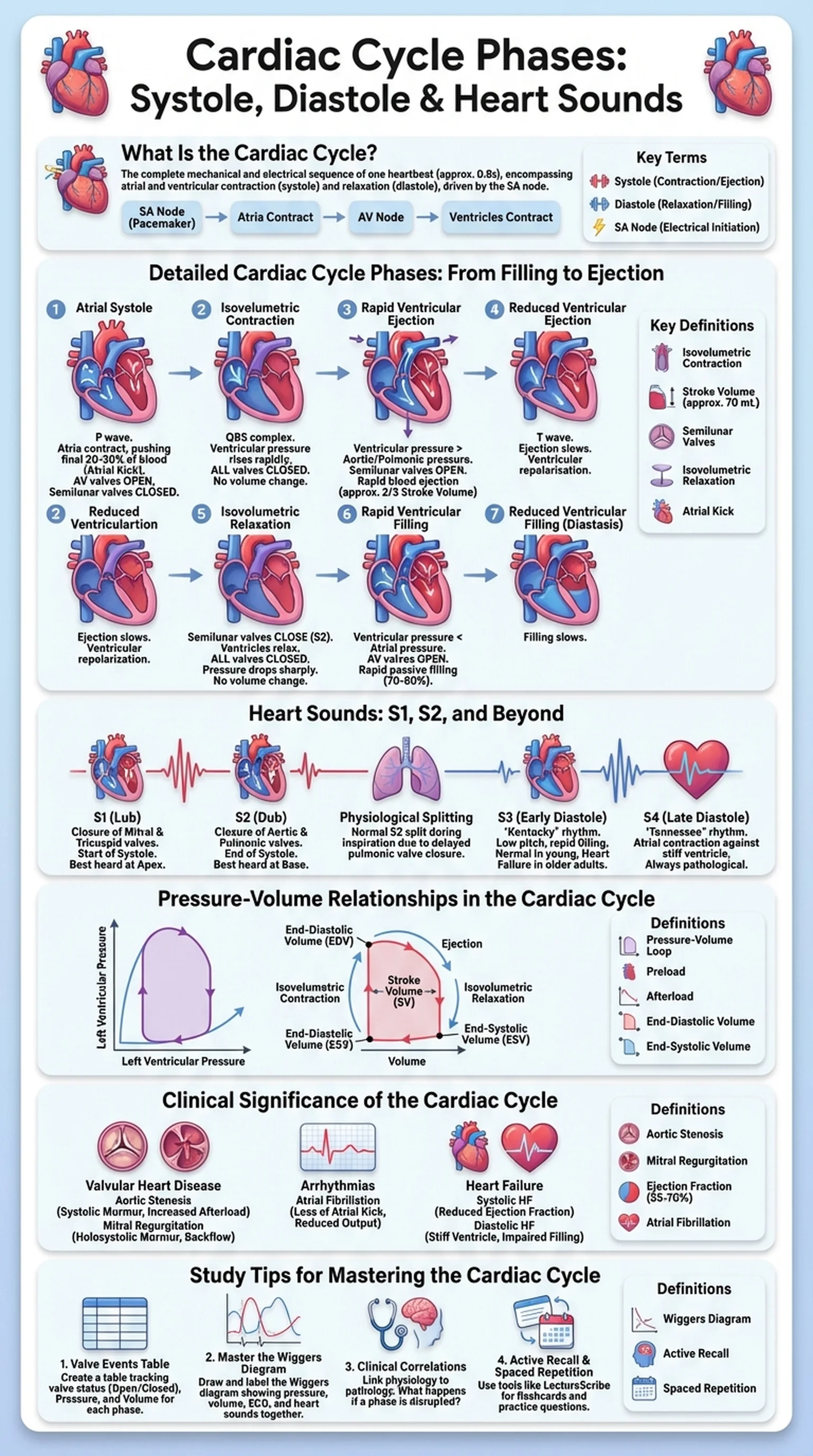

The cardiac cycle is the complete sequence of mechanical and electrical events that occurs from the beginning of one heartbeat to the beginning of the next. Each cardiac cycle lasts approximately 0.8 seconds at a resting heart rate of 75 beats per minute, and it encompasses every contraction and relaxation phase of the atria and ventricles. Understanding the cardiac cycle is essential for students of anatomy, physiology, cardiology, and nursing, as it forms the basis for interpreting heart sounds, electrocardiograms, and hemodynamic measurements.

At its core, the cardiac cycle can be divided into two major periods: systole and diastole. Systole refers to the phase of ventricular contraction, during which blood is ejected from the ventricles into the pulmonary artery and aorta. Diastole refers to the phase of ventricular relaxation, during which the ventricles fill with blood from the atria. While these two terms capture the broad strokes, the cardiac cycle phases are more nuanced, involving distinct sub-phases that describe precise valve movements, pressure changes, and volume shifts within the heart chambers.

The cardiac cycle is driven by the intrinsic electrical conduction system of the heart, beginning with the sinoatrial (SA) node, which generates spontaneous action potentials. These electrical impulses propagate through the atria, the atrioventricular (AV) node, the bundle of His, and the Purkinje fibers, coordinating the sequential contraction of atrial and ventricular muscle. The mechanical events of the cardiac cycle are therefore tightly coupled to the electrical events recorded on an ECG, making the cardiac cycle a cornerstone concept in cardiovascular physiology.

Key Terms

The complete sequence of contraction and relaxation events that occurs during one heartbeat, encompassing both systole and diastole.

The phase of the cardiac cycle during which the ventricles contract and eject blood into the arteries.

The phase of the cardiac cycle during which the ventricles relax and fill with blood from the atria.

The natural pacemaker of the heart, located in the right atrium, that initiates the electrical impulse for each cardiac cycle.