What Is the Cell Membrane?

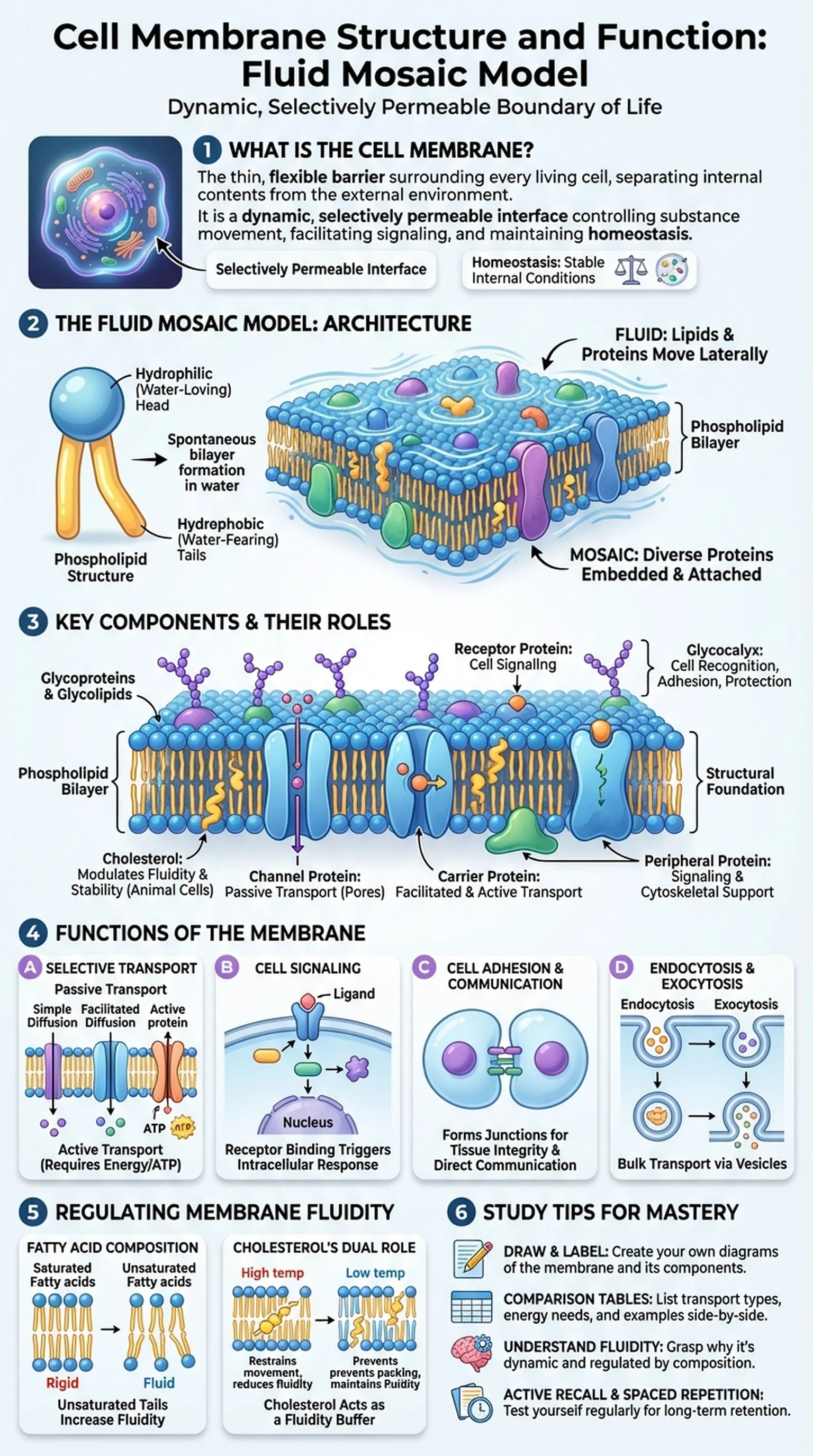

The cell membrane, also known as the plasma membrane, is the thin, flexible barrier that surrounds every living cell and separates its internal contents from the external environment. This structure is far more than a passive boundary; it is a dynamic, selectively permeable interface that controls the movement of substances into and out of the cell, facilitates cell signaling, and maintains the internal conditions necessary for life. Understanding cell membrane structure is foundational to biology, biochemistry, and medicine.

The cell membrane is composed primarily of lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates arranged in a specific architecture described by the fluid mosaic model. This model, proposed by Singer and Nicolson in 1972, describes the membrane as a two-dimensional fluid in which lipid and protein molecules diffuse laterally. The term "mosaic" refers to the diverse collection of proteins embedded within and attached to the lipid layer, creating a patchwork of molecular components with specialized functions.

The importance of the cell membrane cannot be overstated. Without it, cells could not maintain homeostasis, the stable internal environment necessary for enzymatic reactions, DNA replication, and protein synthesis. The membrane's selective permeability ensures that essential nutrients enter the cell while waste products and potentially harmful substances are kept out or expelled. Every process in cell biology, from energy metabolism to immune response, depends on the integrity and functionality of this remarkable structure. Diseases such as cystic fibrosis and certain cancers are directly linked to defects in cell membrane proteins, underscoring the clinical relevance of understanding how the membrane is built and how it works.

Key Terms

The selectively permeable lipid bilayer that encloses the cell and regulates the transport of substances between the cell's interior and exterior.

Another term for the cell membrane; the outermost boundary of animal cells.

The property of the cell membrane that allows certain molecules to pass through while restricting others.

The maintenance of stable internal conditions within a cell or organism despite changes in the external environment.