What Is Protein Synthesis?

Protein synthesis is the biological process by which cells build proteins from amino acids using the genetic instructions encoded in DNA. Proteins are the workhorses of the cell, performing an enormous range of functions including catalyzing metabolic reactions (enzymes), providing structural support (collagen, keratin), transporting molecules (hemoglobin), defending against pathogens (antibodies), and regulating gene expression (transcription factors). Understanding protein synthesis is therefore central to understanding how cells function, grow, divide, and respond to their environment.

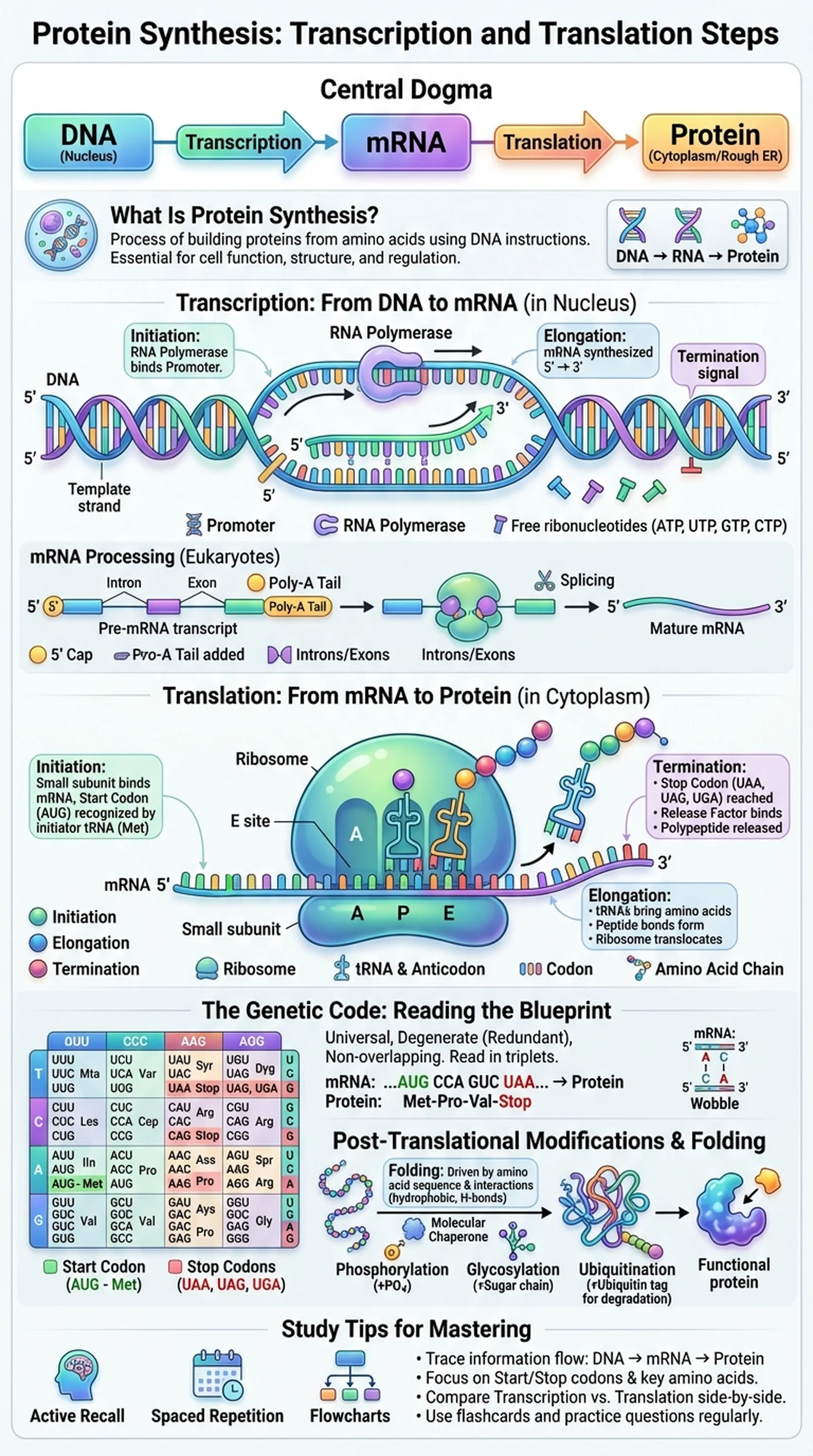

The process of protein synthesis occurs in two major stages: transcription and translation. During transcription, the information in a gene's DNA sequence is copied into a messenger RNA (mRNA) molecule. During translation, the mRNA sequence is read by ribosomes, which assemble amino acids into a polypeptide chain according to the genetic code. These two stages are the core protein synthesis steps that connect genotype to phenotype, converting the abstract information stored in DNA into the functional molecules that carry out cellular activities.

Protein synthesis is a foundational topic in molecular biology, genetics, and biochemistry. It is the molecular basis of the central dogma of molecular biology, which states that genetic information flows from DNA to RNA to protein. Errors in protein synthesis can lead to dysfunctional proteins, which are implicated in numerous diseases including sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, and many forms of cancer. A thorough understanding of how transcription and translation work is essential for any student preparing for exams in biology or the medical sciences.

Key Terms

The cellular process of building proteins from amino acids based on the genetic instructions encoded in DNA, involving transcription and translation.

The principle that genetic information flows from DNA to RNA to protein through the processes of transcription and translation.

A segment of DNA that contains the instructions for building a specific protein or functional RNA molecule.

The building blocks of proteins; twenty different amino acids are joined in specific sequences during translation to form polypeptide chains.