What Is the Central Dogma of Molecular Biology?

The central dogma of molecular biology describes the flow of genetic information within a biological system. First articulated by Francis Crick in 1958 and refined in a landmark 1970 Nature paper, the central dogma states that information flows from DNA to RNA to protein. This directional framework—sometimes summarized as DNA to RNA to protein—provides the conceptual backbone for understanding how genotype gives rise to phenotype.

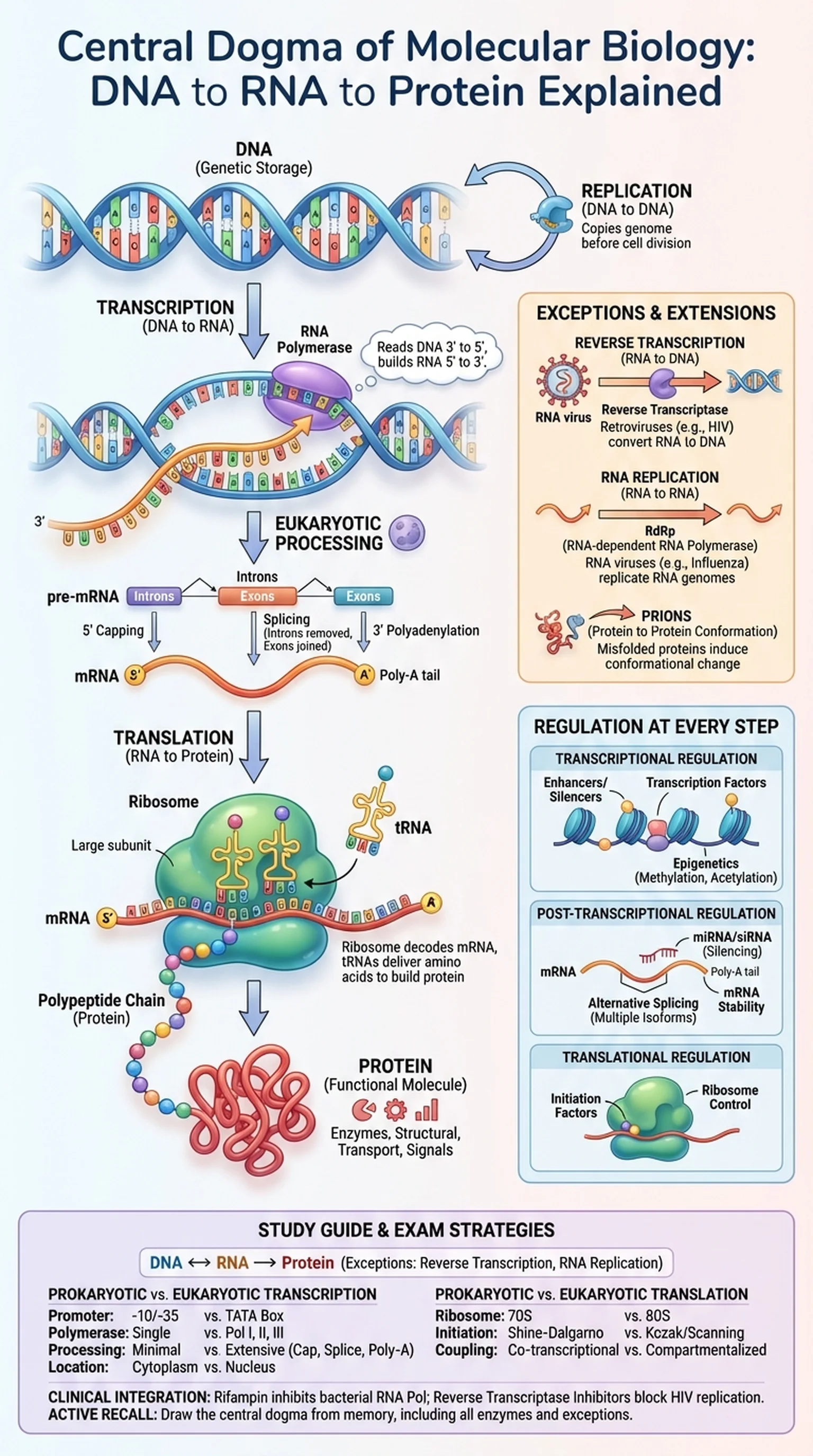

At its simplest, the central dogma involves three information-transfer processes. DNA replication copies DNA into DNA, preserving the genome across cell divisions. Transcription converts a DNA sequence into a complementary RNA molecule. Translation decodes the messenger RNA (mRNA) sequence into a polypeptide chain—a protein. Together, transcription and translation constitute the gene expression pathway that connects the static information stored in DNA to the dynamic functional molecules (proteins) that carry out cellular work.

Crick was careful to define the central dogma not as a simple sequence of events but as a statement about the direction of detailed sequence information transfer. The central dogma asserts that once information has been translated into protein, it cannot flow back to nucleic acid. In other words, proteins do not serve as templates for RNA or DNA synthesis. This distinction is important because it permits reverse transcription (RNA to DNA, carried out by retroviruses) and RNA replication (RNA to RNA, carried out by some RNA viruses) while still preserving the core principle.

The central dogma of molecular biology is arguably the single most important organizing principle in the life sciences. It links genetics (the study of DNA inheritance) to biochemistry (the study of protein function) and provides the framework for modern biotechnology, including gene therapy, mRNA vaccines, CRISPR genome editing, and recombinant protein production. For students preparing for the MCAT, USMLE, or graduate-level biology courses, a deep understanding of the central dogma—and its exceptions—is indispensable.

Key Terms

The principle that genetic information flows from DNA to RNA to protein, and that sequence information cannot transfer from protein back to nucleic acid.

The process by which the information encoded in a gene is used to synthesize a functional gene product, typically a protein, through transcription and translation.

The process of copying a gene's DNA sequence into a complementary RNA molecule by RNA polymerase.

The process by which ribosomes decode mRNA into a polypeptide chain using transfer RNAs that carry specific amino acids.