What Is DNA Replication?

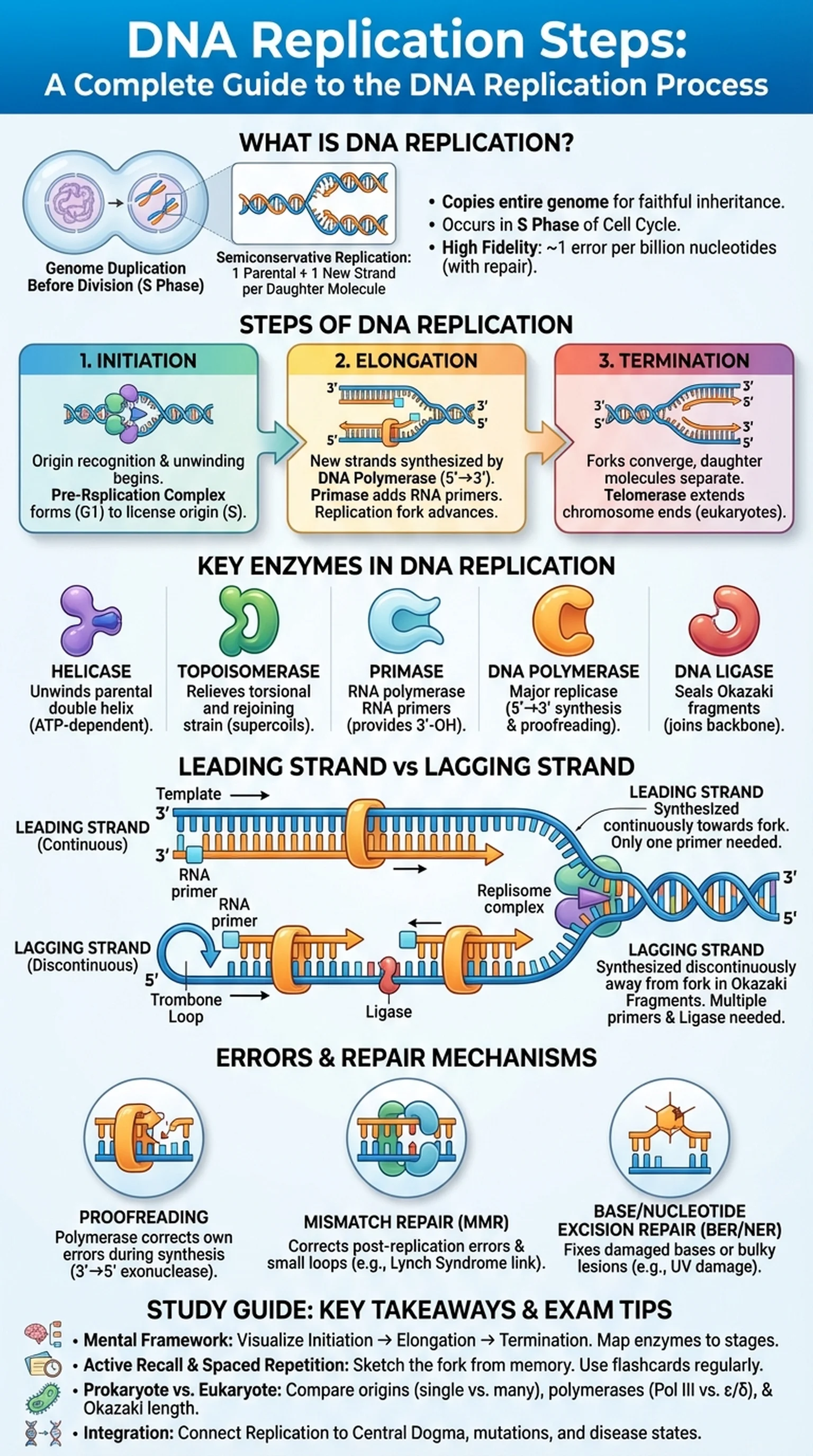

DNA replication is the biological process by which a cell duplicates its entire genome before division, ensuring that each daughter cell receives a faithful copy of the genetic information. Because every cell in a multicellular organism carries the same DNA sequence, understanding the DNA replication process is foundational to molecular biology, genetics, and medicine.

At its core, DNA replication follows the principle of semiconservative replication, a model first demonstrated by the Meselson-Stahl experiment in 1958. In semiconservative replication, each of the two parental strands serves as a template for the synthesis of a new complementary strand. The result is two identical double-stranded DNA molecules, each consisting of one original (parental) strand and one newly synthesized strand. This elegant mechanism preserves genetic fidelity across generations of cell division.

DNA replication occurs during the S phase of the cell cycle, prior to mitosis or meiosis. In prokaryotes such as Escherichia coli, replication begins at a single origin of replication and proceeds bidirectionally around the circular chromosome. Eukaryotic genomes, being much larger and organized into linear chromosomes, contain thousands of replication origins that fire in a coordinated temporal program. Despite these organizational differences, the fundamental DNA replication steps are conserved across all domains of life.

The accuracy of DNA replication is remarkable. The error rate in human cells is approximately one mistake per billion nucleotides copied, thanks to the combined action of polymerase proofreading and post-replicative mismatch repair systems. When these safeguards fail, mutations accumulate and can lead to diseases including cancer. Understanding every stage of the DNA replication process therefore has direct clinical relevance, from pharmacology—many antibiotics and chemotherapeutics target replication enzymes—to genetic counseling and forensic science.

Key Terms

The biological process by which a cell copies its entire DNA genome to produce two identical DNA molecules before cell division.

The mode of DNA replication in which each daughter molecule contains one parental strand and one newly synthesized strand.

A specific DNA sequence where replication is initiated, recognized by initiator proteins that separate the two strands.

The phase of the cell cycle during which DNA synthesis (replication) occurs, situated between the G1 and G2 phases.