Overview of Diabetes and Its Pharmacological Management

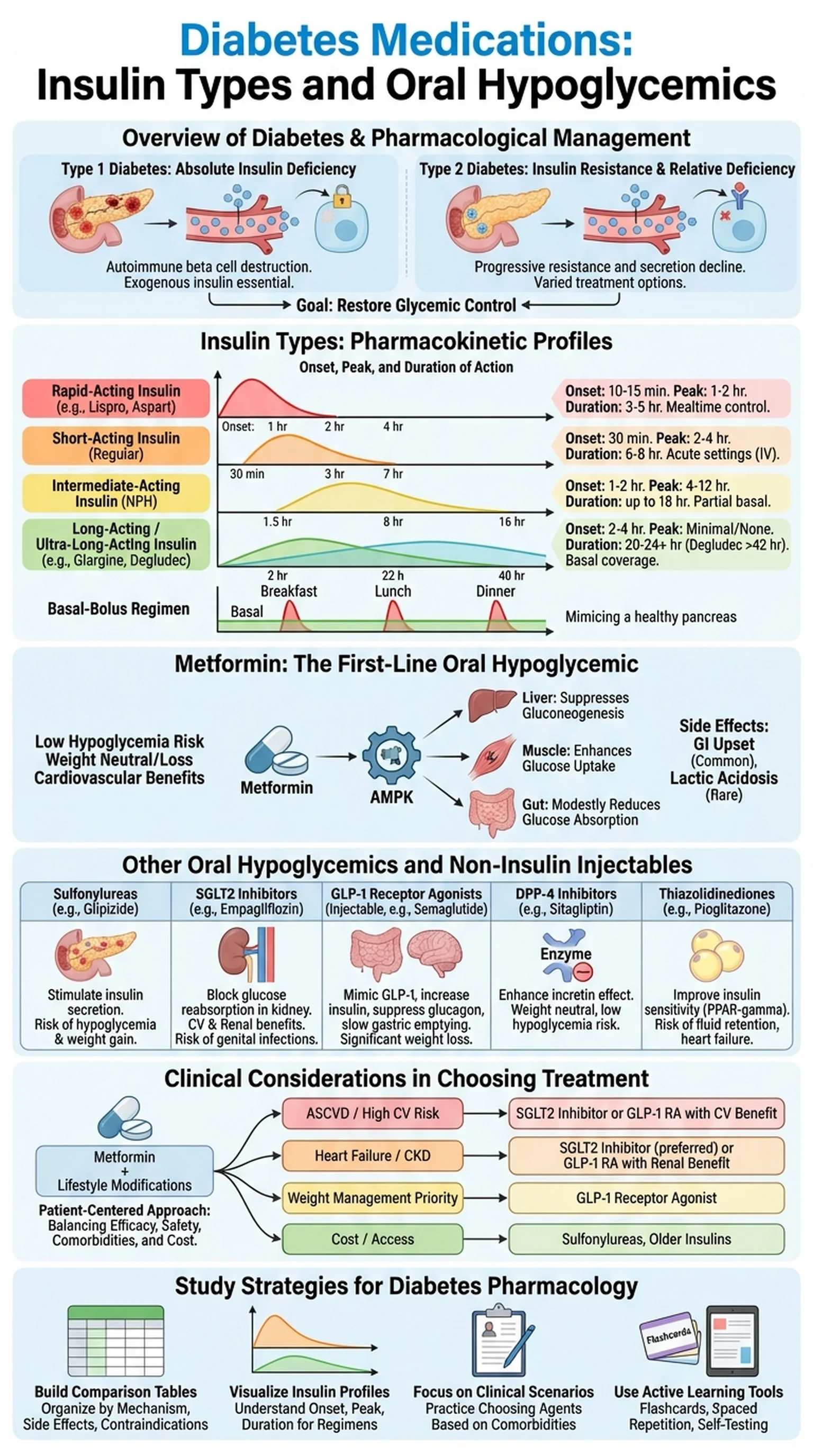

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by persistent hyperglycemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. The two major forms, Type 1 and Type 2, differ fundamentally in their pathophysiology and therefore require distinct pharmacological approaches. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition in which pancreatic beta cells are destroyed, leading to absolute insulin deficiency. Type 2 diabetes, which accounts for roughly 90 percent of all cases, involves progressive insulin resistance and a relative decline in insulin secretion over time.

Diabetes medications encompass a broad spectrum of agents designed to restore glycemic control. For Type 1 patients, exogenous insulin is the cornerstone of diabetes treatment, since the body can no longer produce its own. For Type 2 patients, the therapeutic landscape is far more varied, ranging from oral hypoglycemics such as metformin and sulfonylureas to injectable agents including GLP-1 receptor agonists and, eventually, insulin itself when oral agents fail to maintain adequate control.

Understanding the pharmacology of these agents is critical for medical students, nursing students, and pharmacy students alike. The choice of diabetes treatment depends on multiple factors: the type and severity of diabetes, the patient's comorbidities, risk of hypoglycemia, cost considerations, and patient preference. Modern guidelines emphasize a patient-centered approach in which clinicians select from the available diabetes medications based on individual risk-benefit profiles. This section provides the foundation for understanding the insulin types and oral hypoglycemics that form the pillars of diabetes pharmacotherapy.

Key Terms

A group of metabolic diseases characterized by chronic hyperglycemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both.

Abnormally elevated blood glucose levels, the hallmark of uncontrolled diabetes.

A condition in which target tissues such as muscle, liver, and adipose fail to respond adequately to normal circulating levels of insulin.

Endocrine cells located in the islets of Langerhans of the pancreas that produce and secrete insulin.