Overview of the Digestive System

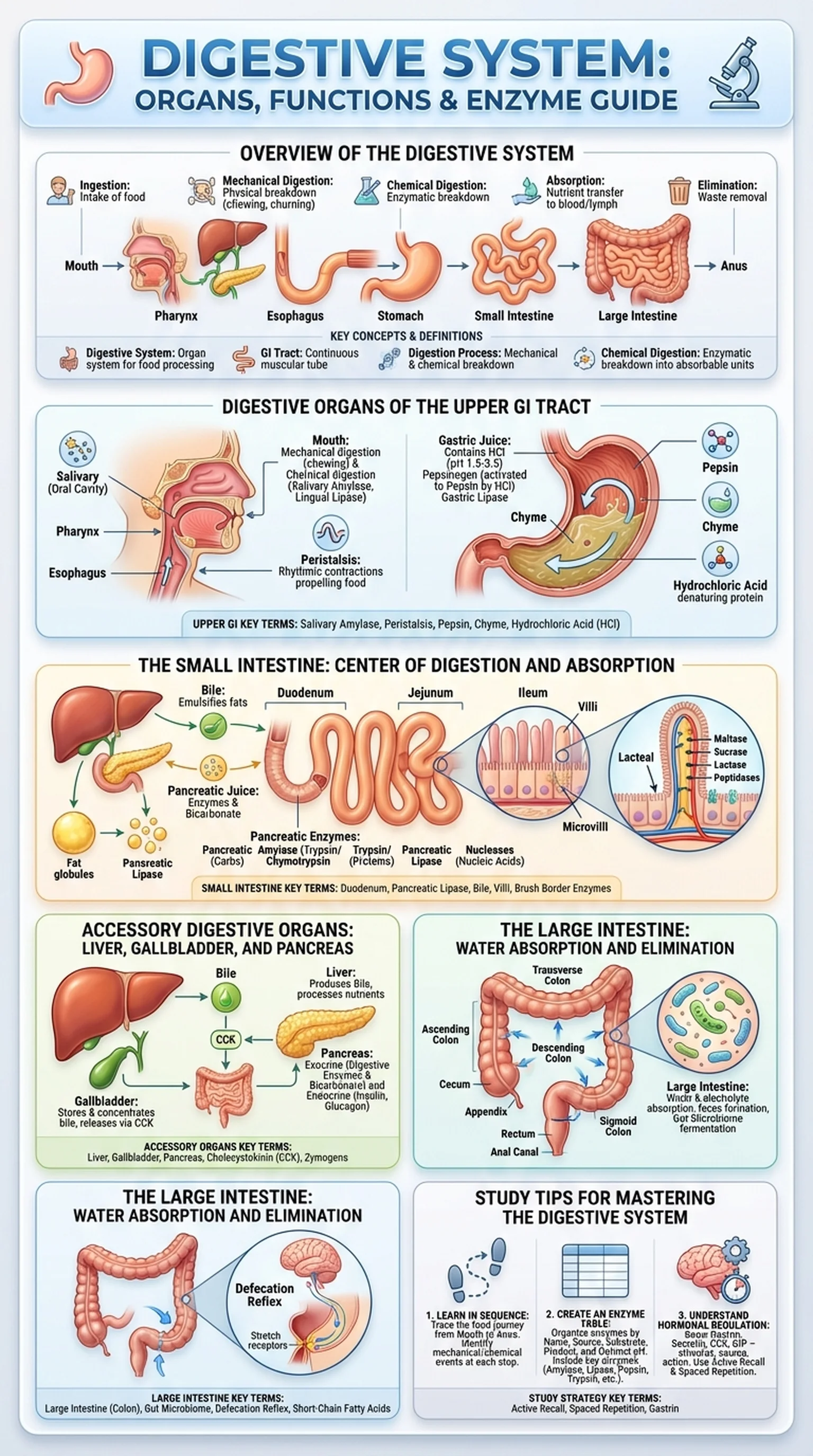

The digestive system is a complex organ system responsible for breaking down food into nutrients that the body can absorb and use for energy, growth, and cellular repair. Extending from the mouth to the anus, the digestive system encompasses a continuous muscular tube known as the gastrointestinal tract, or GI tract, along with several accessory organs that secrete digestive enzymes and other substances essential for the digestion process.

The primary functions of the digestive system include ingestion, mechanical digestion, chemical digestion, absorption, and elimination. Ingestion is the intake of food through the mouth. Mechanical digestion involves the physical breakdown of food into smaller pieces through chewing, churning, and segmentation. Chemical digestion uses digestive enzymes and other chemicals to break down macromolecules such as proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids into their absorbable subunits. Absorption is the transfer of nutrients from the GI tract lumen into the bloodstream and lymphatic system. Finally, elimination is the removal of indigestible waste from the body as feces.

Understanding the digestive system is foundational for students of anatomy, physiology, nutrition, and medicine. The digestive organs work in a coordinated sequence, each contributing specific mechanical or chemical actions to the overall digestion process. Disruptions at any point along the GI tract can lead to clinical conditions ranging from gastroesophageal reflux disease and peptic ulcers to malabsorption syndromes and inflammatory bowel disease. By studying the structure and function of each digestive organ, students gain the knowledge needed to understand both normal physiology and the pathophysiology of gastrointestinal disorders.

Key Terms

The organ system responsible for the ingestion, digestion, absorption, and elimination of food and nutrients.

The gastrointestinal tract; the continuous muscular tube from the mouth to the anus through which food passes during digestion.

The complete sequence of mechanical and chemical events that break down food into absorbable nutrients within the digestive system.

The enzymatic breakdown of macromolecules into smaller molecules that can be absorbed across the intestinal lining.