Introduction to Drug Receptor Interactions

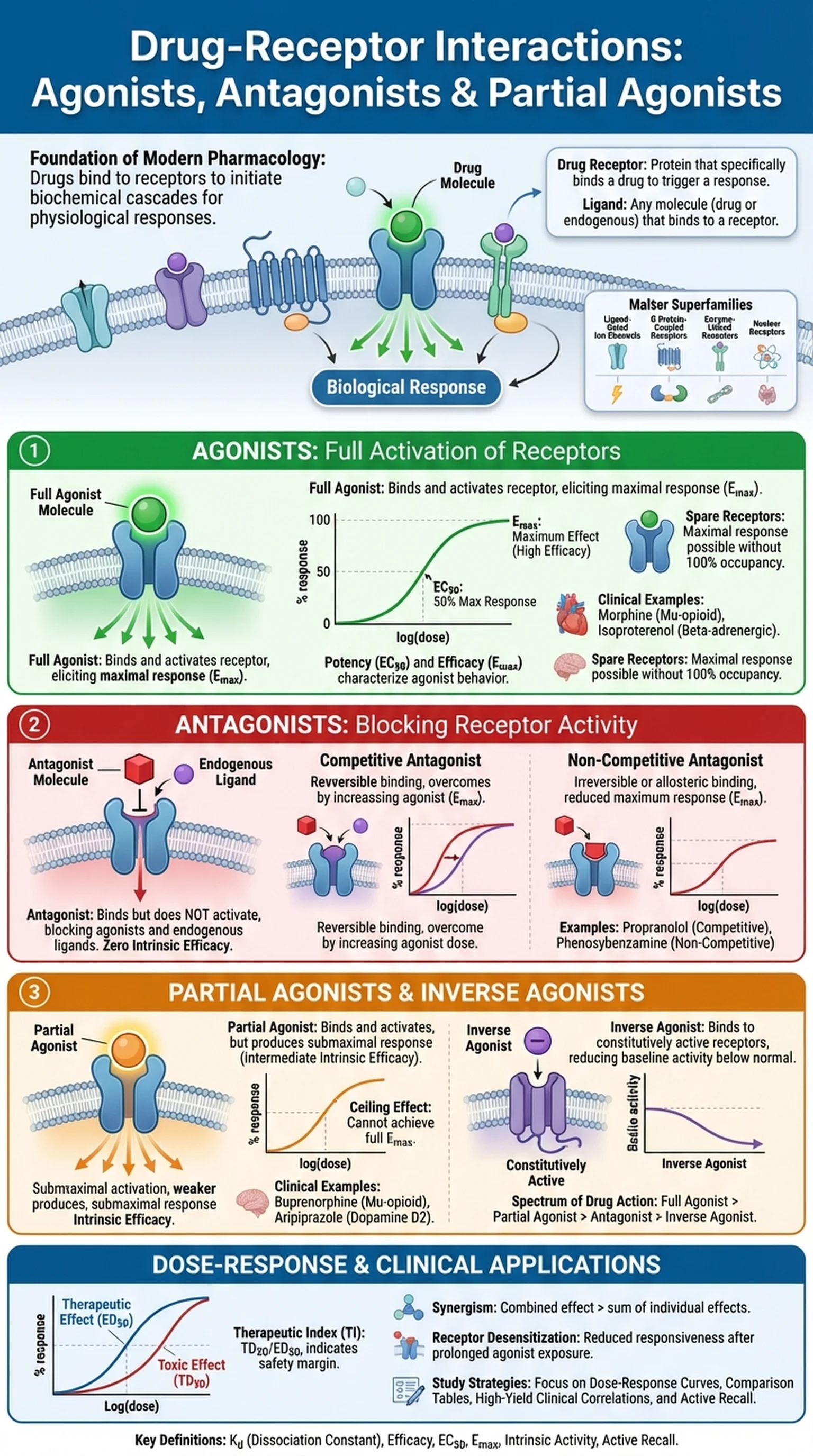

Drug receptor interactions form the foundation of modern pharmacology and explain how medications produce their therapeutic effects in the body. A receptor is a specialized protein, typically located on the cell surface or within the cytoplasm, that binds to a specific molecule known as a ligand. When a drug binds to its target receptor, it initiates a cascade of biochemical events that ultimately lead to a physiological response. Understanding drug receptor interactions is essential for predicting drug behavior, designing new therapies, and managing clinical outcomes.

The concept of receptor pharmacology dates back to the early twentieth century, when Paul Ehrlich and John Newport Langley independently proposed that drugs exert their effects by interacting with discrete cellular components. Today, receptor pharmacology has evolved into a sophisticated discipline that encompasses molecular modeling, quantitative binding assays, and structure-activity relationship studies. At its core, however, the principle remains the same: a drug must bind to a receptor to produce an effect, and the nature of that binding determines whether the drug activates or inhibits the receptor.

Receptors can be classified into four major superfamilies: ligand-gated ion channels, G protein-coupled receptors, enzyme-linked receptors, and nuclear receptors. Each superfamily has distinct structural features and signaling mechanisms, but they all share the common property of recognizing specific ligands with high affinity and selectivity. The interaction between a drug and its receptor is governed by the law of mass action, meaning that the rate of binding depends on the concentrations of both the drug and the receptor. This reversible equilibrium is described by the dissociation constant (Kd), which reflects the affinity of a drug for its receptor.

Key Terms

A specialized protein on or within a cell that specifically binds a drug or endogenous ligand, triggering a biological response.

Any molecule that binds to a receptor, including endogenous substances like neurotransmitters and exogenous substances like drugs.

The branch of pharmacology focused on understanding how drugs interact with receptors to produce therapeutic and adverse effects.

A measure of the affinity between a drug and its receptor; a lower Kd indicates higher binding affinity.