Introduction to Ear Anatomy

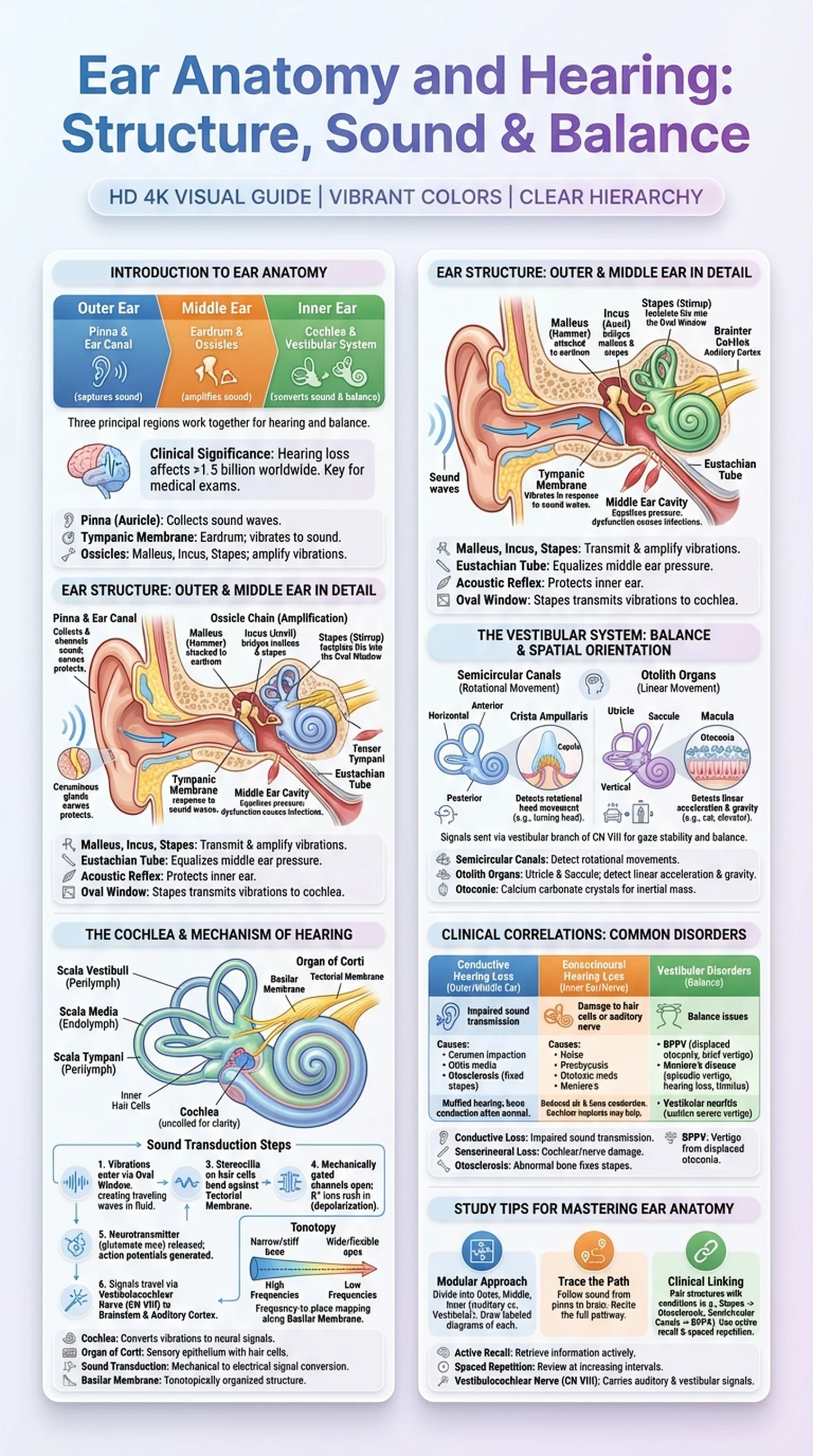

Ear anatomy is a rich and multifaceted subject that encompasses not only the structures responsible for hearing but also those that govern balance and spatial orientation. The human ear is divided into three principal regions: the outer ear, the middle ear, and the inner ear. Each region contains specialized structures that work in concert to capture sound waves from the environment, convert them into mechanical vibrations, transform those vibrations into electrical signals, and relay those signals to the auditory cortex of the brain.

Understanding ear structure is essential for students of anatomy, audiology, otolaryngology, and neuroscience. The ear appears on virtually every major medical and health sciences examination, from the USMLE and MCAT to audiology certification boards. Its clinical significance is vast: hearing loss affects over 1.5 billion people worldwide, and vestibular disorders are among the most common complaints seen in primary care settings.

The outer ear consists of the pinna (auricle) and the external auditory canal, which together funnel sound toward the tympanic membrane. The middle ear is an air-filled cavity containing the three smallest bones in the human body, the ossicles, which mechanically amplify sound vibrations. The inner ear houses the cochlea, the spiral-shaped organ responsible for sound transduction, and the vestibular system, which detects head position and movement. This introductory overview of ear anatomy sets the stage for a deeper exploration of how each component contributes to the remarkable processes of hearing and balance.

Key Terms

The study of the structural components of the ear, divided into the outer ear, middle ear, and inner ear, each serving distinct roles in hearing and balance.

The external, visible portion of the ear that collects and directs sound waves into the external auditory canal.

The eardrum; a thin, semitransparent membrane separating the outer ear from the middle ear that vibrates in response to sound waves.

The three small bones of the middle ear (malleus, incus, stapes) that transmit and amplify vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the inner ear.