Introduction to Eye Anatomy

Eye anatomy is one of the most elegant topics in human biology, revealing how a small organ barely an inch in diameter can convert electromagnetic radiation into the rich experience of sight. The human eye functions as a biological camera, but its complexity far surpasses any man-made optical device. Understanding eye structure is foundational for students of anatomy, ophthalmology, neuroscience, and optometry, and it appears frequently on exams such as the USMLE, MCAT, and NBEO.

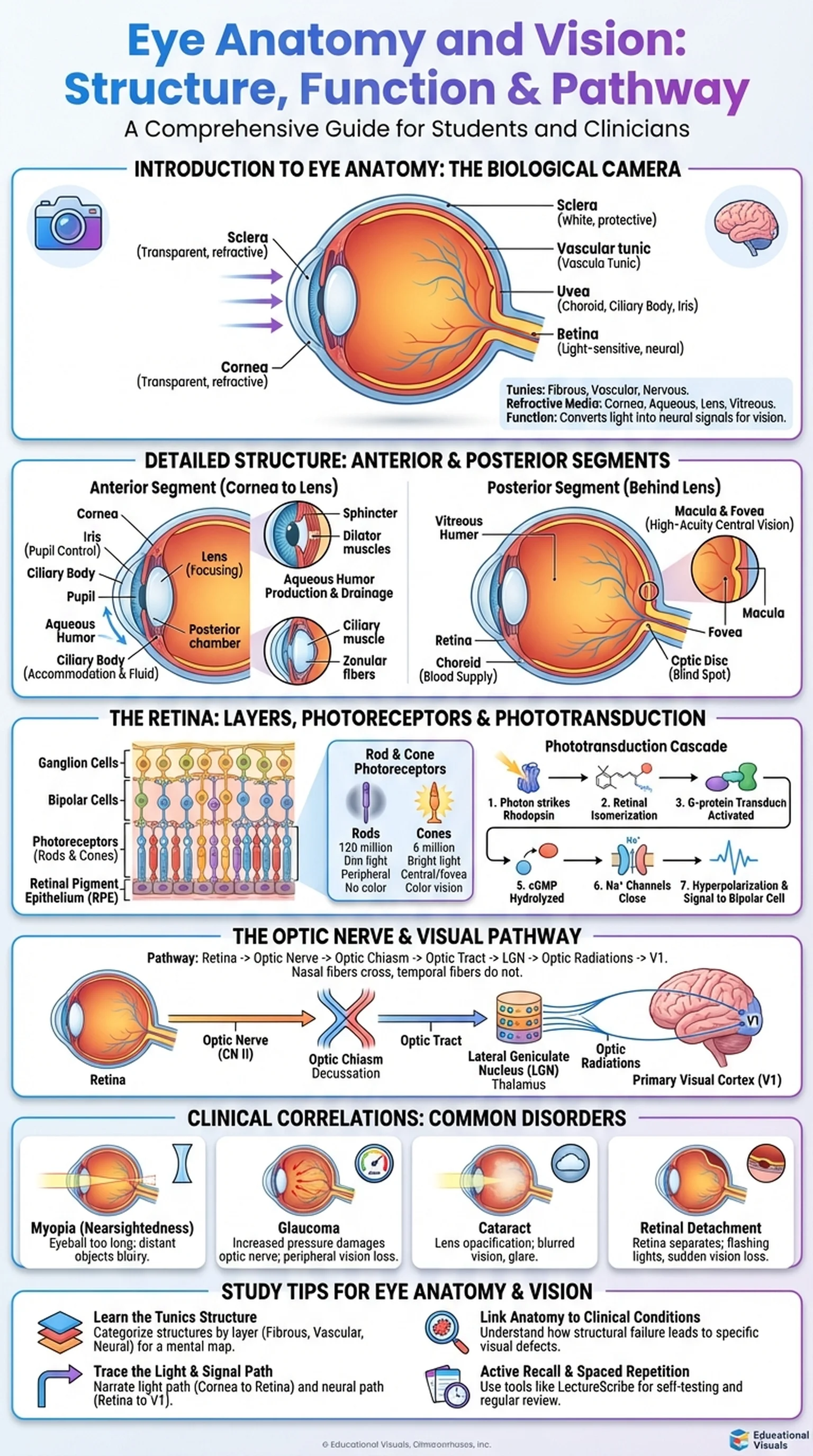

The eye sits within the bony orbit of the skull, cushioned by orbital fat and supported by six extraocular muscles that control its movement. The globe itself is composed of three concentric layers, or tunics. The outermost fibrous tunic includes the sclera and the cornea. The middle vascular tunic, also called the uvea, consists of the choroid, ciliary body, and iris. The innermost nervous tunic is the retina, the light-sensitive layer that initiates the process of vision. Each of these layers plays a distinct role in protecting the eye, nourishing its tissues, and converting light into neural signals.

Beyond the tunics, the eye contains refractive media that bend light to focus it on the retina. These include the cornea, aqueous humor, crystalline lens, and vitreous humor. The cornea provides about two-thirds of the eye's total refractive power, while the lens fine-tunes focus through a process called accommodation. Together, these structures ensure that light from objects at varying distances converges precisely on the photoreceptor cells of the retina, enabling clear vision across a wide range of conditions.

Key Terms

The study of the structural components of the eye, including its three tunics, refractive media, and accessory structures.

The tough, white outer layer of the eye that provides structural support and protection for the internal components.

The transparent, avascular anterior portion of the fibrous tunic that provides the majority of the eye's refractive power.

The vascular middle layer of the eye comprising the choroid, ciliary body, and iris.

The process by which the ciliary muscle changes the shape of the lens to focus on objects at different distances.