What Is the Electron Transport Chain?

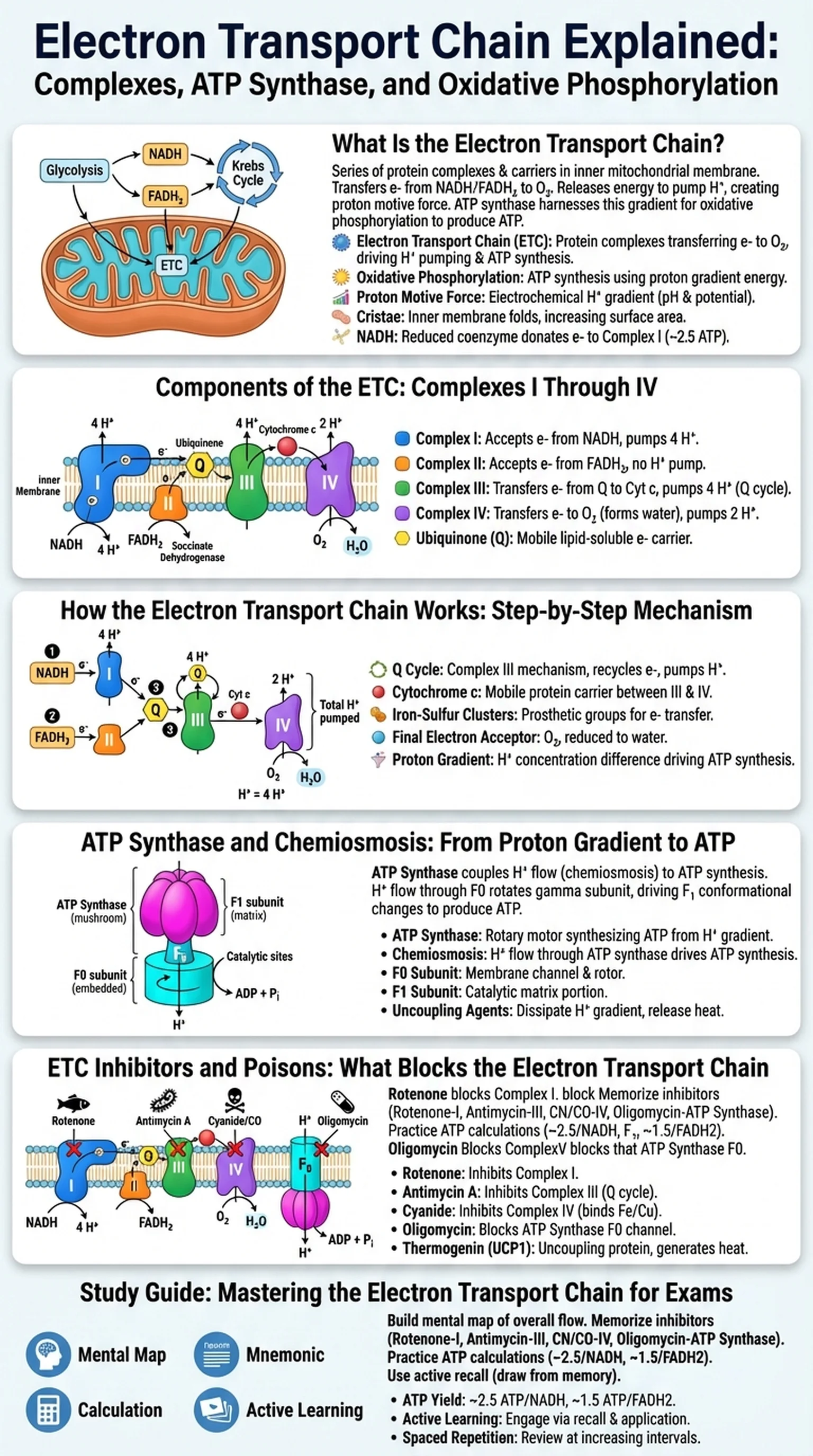

The electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and mobile electron carriers embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane that transfer electrons from NADH and FADH2 to molecular oxygen. This sequential electron transfer releases energy that is used to pump protons (H+ ions) across the inner mitochondrial membrane, creating an electrochemical gradient known as the proton motive force. The energy stored in this gradient is then harnessed by ATP synthase to produce ATP through a process called oxidative phosphorylation. Together, the electron transport chain and oxidative phosphorylation account for the vast majority of ATP generated during aerobic cellular respiration.

To have the electron transport chain explained in its proper context, you must understand its position within the overall scheme of cellular respiration. Glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and the ETC form a metabolic relay: glycolysis produces 2 NADH per glucose, the Krebs cycle produces 6 NADH and 2 FADH2, and all of these reduced coenzymes deliver their electrons to the electron transport chain. The ETC is therefore the culmination of carbon fuel oxidation, converting the chemical energy stored in NADH and FADH2 into a usable form of cellular energy.

The electron transport chain is located exclusively in the inner mitochondrial membrane, which is highly folded into structures called cristae to maximize surface area. This arrangement allows a large number of ETC complexes to be packed into a relatively small space, increasing the cell's capacity for oxidative phosphorylation. In prokaryotes, which lack mitochondria, the ETC is located in the plasma membrane. The universal presence of electron transport chains across life's domains underscores their fundamental importance in bioenergetics.

Key Terms

A series of protein complexes in the inner mitochondrial membrane that transfer electrons from NADH and FADH2 to oxygen, driving proton pumping and ATP synthesis.

The process by which ATP is synthesized using the energy of the proton gradient established by the electron transport chain.

The electrochemical gradient of protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane, composed of a pH gradient and a membrane potential.

The folds of the inner mitochondrial membrane that increase surface area for electron transport chain complexes and ATP synthase.

A reduced coenzyme that donates electrons to Complex I of the electron transport chain, yielding approximately 2.5 ATP per molecule.