What Is Enzyme Inhibition?

Enzyme inhibition is the process by which specific molecules reduce or eliminate the catalytic activity of enzymes. Enzyme inhibitors are substances that bind to enzymes and decrease their ability to convert substrates into products. This phenomenon is fundamental to biochemistry and has far-reaching implications in pharmacology, metabolism, and disease. Nearly half of all FDA-approved drugs work by acting as enzyme inhibitors, targeting specific enzymes involved in disease pathways to restore normal physiological function.

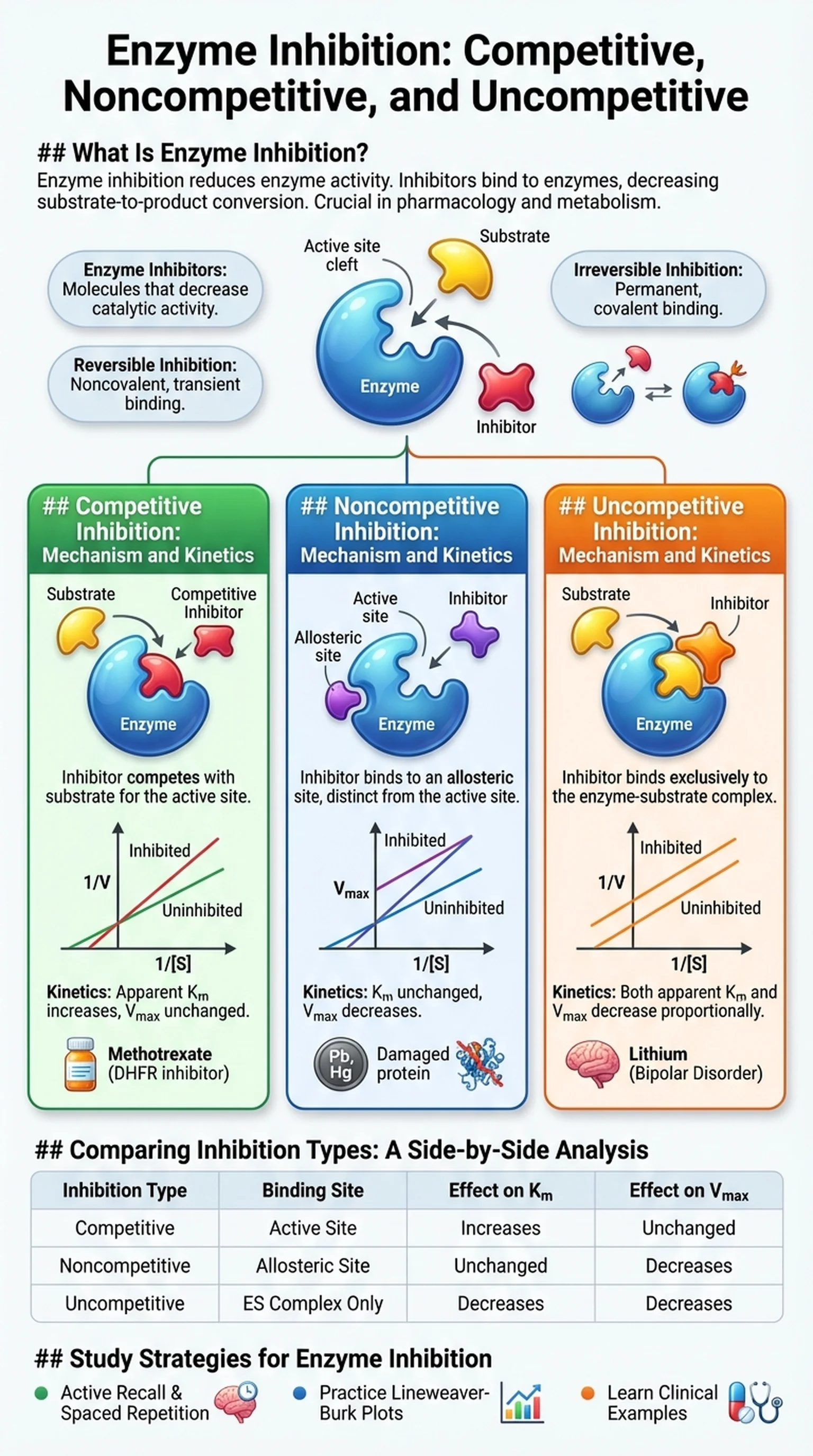

Enzyme inhibition can be broadly divided into two categories: reversible and irreversible. Reversible inhibitors bind to enzymes through noncovalent interactions such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and ionic attractions. Because these interactions are weak and transient, the enzyme can regain full activity once the inhibitor dissociates. Irreversible inhibitors, by contrast, form covalent bonds with amino acid residues in or near the active site, permanently inactivating the enzyme. Aspirin, for example, irreversibly acetylates cyclooxygenase (COX), blocking prostaglandin synthesis and reducing inflammation.

Within the category of reversible inhibition, there are three classical types: competitive inhibition, noncompetitive inhibition, and uncompetitive inhibition. Each type is defined by where the inhibitor binds relative to the substrate and how it affects the kinetic parameters Km and Vmax. Understanding these distinctions is essential for interpreting enzyme kinetic data, designing effective drugs, and answering exam questions on standardized tests like the MCAT and USMLE. The sections that follow provide a detailed analysis of each inhibition type, complete with molecular mechanisms, kinetic consequences, and real-world examples.

Key Terms

The reduction or elimination of enzyme catalytic activity by molecules (inhibitors) that bind to the enzyme and interfere with its function.

Molecules that bind to enzymes and decrease their catalytic activity, classified as reversible or irreversible depending on their binding mechanism.

Inhibition in which the inhibitor binds noncovalently to the enzyme and can dissociate, allowing the enzyme to regain activity.

Inhibition in which the inhibitor forms a permanent covalent bond with the enzyme, leading to permanent loss of catalytic function.