What Is Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium?

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium is a foundational principle of population genetics that describes a theoretical population in which allele frequencies and genotype frequencies remain constant from generation to generation in the absence of evolutionary influences. Independently derived by mathematician G. H. Hardy and physician Wilhelm Weinberg in 1908, the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium provides a null model against which real populations can be compared to detect the action of evolutionary forces.

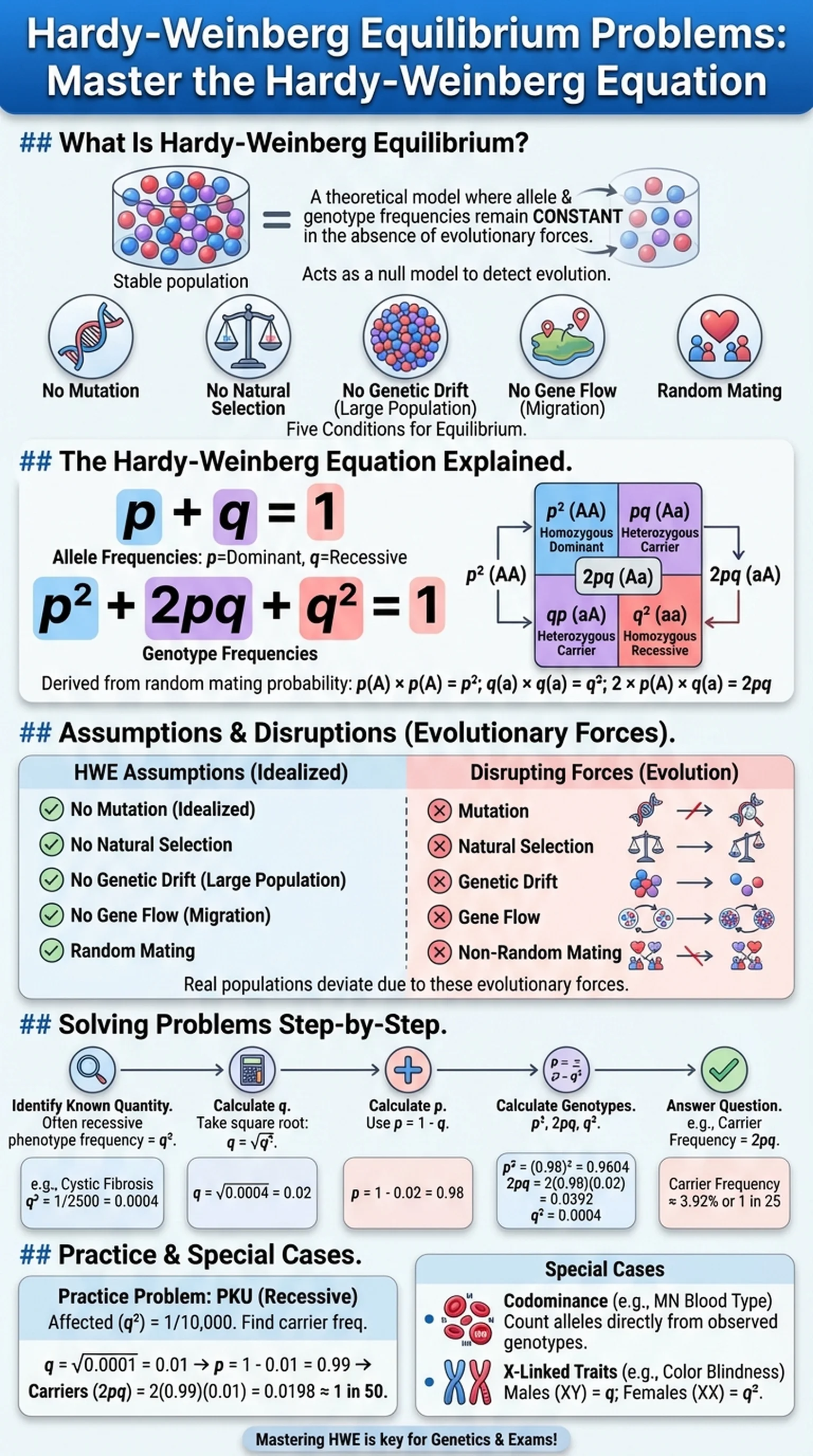

In a population at Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, five conditions must be met: no mutation, no natural selection, no genetic drift (infinitely large population size), no gene flow (migration), and random mating. When all five assumptions hold, the allele frequency of every gene in the population remains unchanged across generations, and genotype frequencies can be predicted directly from allele frequencies using the Hardy-Weinberg equation.

The practical importance of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium lies in its role as a benchmark. By comparing observed genotype frequencies in a real population to those expected under equilibrium, geneticists can infer which evolutionary forces are at work. If a population deviates significantly from Hardy-Weinberg expectations, at least one of the five assumptions is being violated—perhaps natural selection is favoring one allele, or genetic drift is causing random fluctuations in a small population, or non-random mating is altering genotype proportions.

For medical genetics, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium is used routinely to estimate carrier frequencies for autosomal recessive disorders. If one in 10,000 individuals is affected (genotype frequency q² = 1/10,000), the allele frequency q = 1/100 and the carrier frequency 2pq ≈ 2/100, or approximately 2% of the population. This calculation is frequently tested on the MCAT and USMLE and is a standard tool in genetic counseling.

Mastering Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium problems begins with understanding the conceptual foundation: a population in equilibrium is not evolving, and any departure from equilibrium signals the presence of one or more evolutionary mechanisms driving changes in allele frequency.

Key Terms

A state in which allele and genotype frequencies in a population remain constant across generations, indicating the absence of evolutionary forces.

The proportion of a specific allele among all copies of that gene in a population, typically denoted as p for the dominant allele and q for the recessive allele.

The branch of genetics that studies the distribution and change of allele frequencies within populations, incorporating the effects of selection, drift, mutation, and migration.

A baseline hypothesis (here, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium) that assumes no evolutionary forces are acting, against which observed data are compared.