Overview of Heart Anatomy

Heart anatomy is one of the most fundamental topics in human biology and medical education. The heart is a muscular organ approximately the size of a closed fist, located in the mediastinum of the thoracic cavity, slightly left of the midline. It is enclosed in a double-walled sac called the pericardium and functions as the central pump of the cardiovascular system, responsible for circulating blood to every tissue in the body. Understanding cardiac anatomy is prerequisite knowledge for courses in physiology, pathology, and clinical medicine.

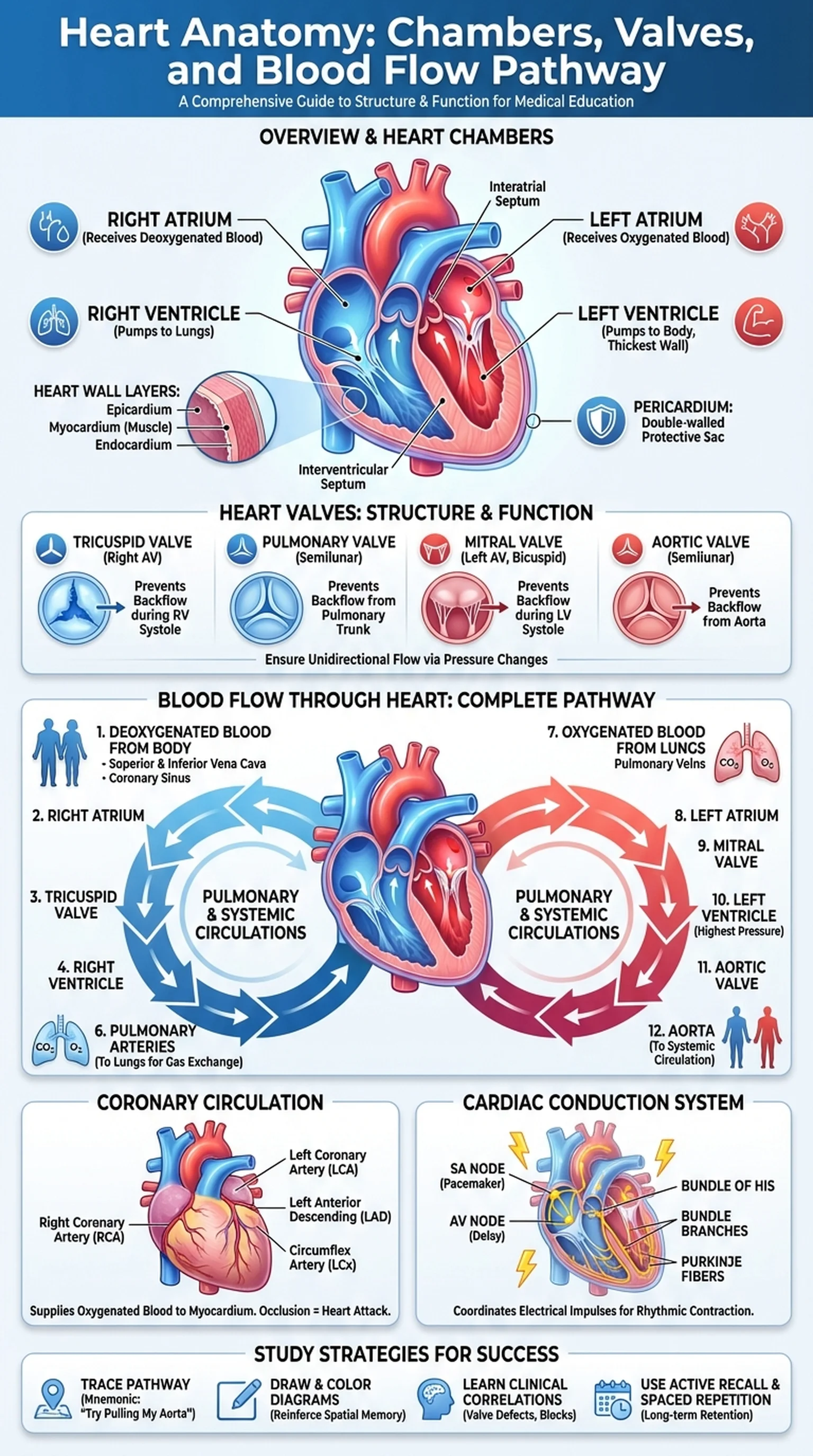

The heart wall consists of three layers: the epicardium (outer layer), the myocardium (thick muscular middle layer), and the endocardium (smooth inner lining). The myocardium is composed of specialized cardiac muscle cells (cardiomyocytes) that are capable of rhythmic, involuntary contraction. The thickness of the myocardium varies by chamber, reflecting the workload of each region. The left ventricle, which pumps blood to the entire systemic circulation, has the thickest myocardium, while the atria, which merely push blood into the ventricles below them, have much thinner walls.

A thorough understanding of heart anatomy requires knowledge of the four heart chambers, the four heart valves, the great vessels, the coronary circulation, and the cardiac conduction system. Together, these structures ensure that blood flow through heart follows a precise unidirectional pathway: deoxygenated blood enters the right side, is pumped to the lungs for gas exchange, returns to the left side, and is then ejected into the systemic circulation. This dual-circuit arrangement, the pulmonary and systemic circulations, is one of the hallmarks of cardiac anatomy in mammals and is central to understanding cardiovascular physiology and disease.

Key Terms

The structural organization of the heart including its chambers, valves, wall layers, great vessels, and conduction system.

The study of the heart's physical structure, encompassing both gross and microscopic features essential for understanding cardiovascular function.

A double-walled fibroserous sac enclosing the heart, consisting of a fibrous outer layer and a serous inner layer that reduces friction during heartbeats.

The thick muscular middle layer of the heart wall composed of cardiomyocytes, responsible for generating the contractile force that pumps blood.