What Is Hemoglobin and How Does It Transport Oxygen?

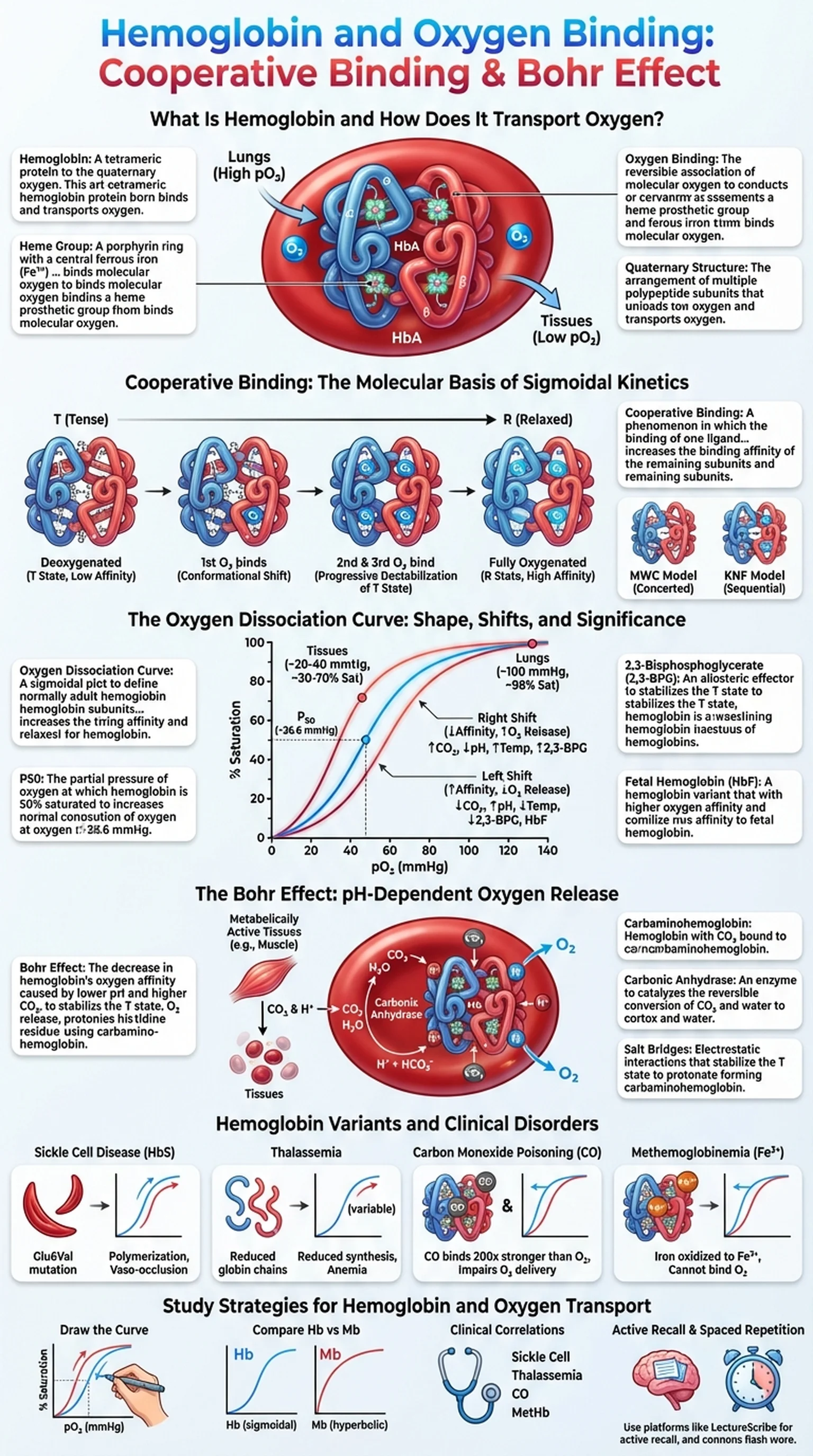

Hemoglobin is a tetrameric metalloprotein found in red blood cells (erythrocytes) that is responsible for transporting oxygen from the lungs to the tissues and facilitating the return of carbon dioxide to the lungs for exhalation. Each hemoglobin molecule consists of four polypeptide subunits, two alpha chains and two beta chains in adult hemoglobin (HbA), and each subunit contains a heme prosthetic group with a central iron atom in the ferrous (Fe2+) state. It is this iron atom that reversibly binds one molecule of O2, giving each hemoglobin tetramer the capacity to carry up to four oxygen molecules simultaneously.

The ability of hemoglobin to bind and release oxygen efficiently is essential for aerobic life. In the lungs, where the partial pressure of oxygen is high, hemoglobin becomes nearly fully saturated with O2. In the peripheral tissues, where oxygen tension is lower and metabolic demand is high, hemoglobin releases its oxygen cargo to supply the cells. This loading and unloading behavior is not a simple on-off switch; instead, it is governed by a sophisticated set of molecular interactions that include cooperative binding, allosteric regulation, and sensitivity to local chemical conditions such as pH, CO2 concentration, and temperature.

Understanding oxygen binding by hemoglobin is foundational for students of biochemistry, physiology, and medicine. Abnormalities in hemoglobin structure or function underlie diseases such as sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, and carbon monoxide poisoning. The principles governing hemoglobin's behavior also illustrate broader biochemical concepts including allostery, protein quaternary structure, and the relationship between structure and function that are central to molecular biology.

Key Terms

A tetrameric protein in red blood cells composed of four subunits, each containing a heme group, that reversibly binds and transports oxygen.

A porphyrin ring with a central ferrous iron (Fe2+) atom that directly binds molecular oxygen in each hemoglobin subunit.

The reversible association of molecular oxygen with the iron atom in hemoglobin's heme group, enabling oxygen transport from lungs to tissues.

The arrangement of multiple polypeptide subunits into a functional protein complex, as seen in hemoglobin's alpha2-beta2 tetramer.