What Is Oxidative Phosphorylation?

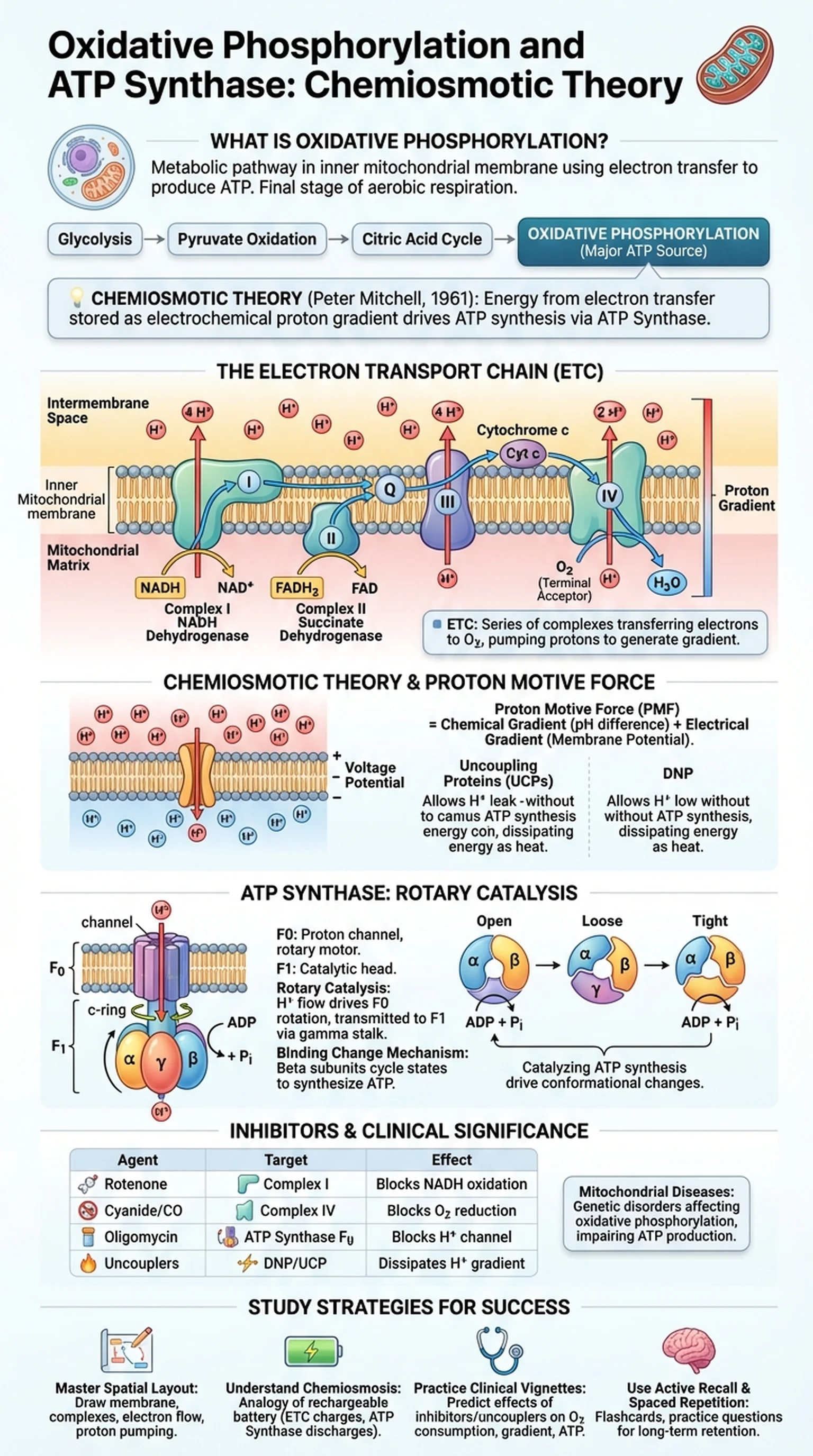

Oxidative phosphorylation is the metabolic pathway through which cells use enzyme complexes and electron transfer to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP). It occurs in the inner mitochondrial membrane and represents the final stage of aerobic cellular respiration, following glycolysis, pyruvate oxidation, and the citric acid cycle. The term "oxidative" refers to the fact that oxygen serves as the final electron acceptor, while "phosphorylation" describes the addition of a phosphate group to ADP to form ATP. Together, these processes account for the vast majority of ATP generated by aerobic organisms.

The concept of oxidative phosphorylation was refined over decades of biochemical research. Peter Mitchell proposed the chemiosmotic theory in 1961, fundamentally changing how scientists understood energy coupling in biological systems. Mitchell's revolutionary insight was that the energy released during electron transfer is not used directly to synthesize ATP. Instead, it is first stored as an electrochemical proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane, and this proton gradient then drives ATP synthesis through a molecular turbine called ATP synthase.

Understanding oxidative phosphorylation is essential for students of biochemistry and medicine because this pathway produces approximately 26 to 28 of the 30 to 32 ATP molecules generated per glucose molecule during complete aerobic respiration. Defects in any component of the system can lead to severe mitochondrial diseases, neurodegeneration, and metabolic failure. The electron transport chain ATP production machinery is therefore one of the most clinically significant biochemical systems in the human body, and a thorough grasp of its mechanism is critical for exams like the MCAT and USMLE.

Key Terms

The metabolic process in which ATP is synthesized using energy released from the transfer of electrons through the electron transport chain to molecular oxygen.

The movement of protons down their electrochemical gradient through ATP synthase, coupling the proton motive force to ATP synthesis.

The difference in hydrogen ion concentration across the inner mitochondrial membrane that stores potential energy for ATP production.

The highly folded membrane housing the electron transport chain complexes and ATP synthase where oxidative phosphorylation occurs.