Overview of the Immune System

The immune system is a highly complex network of cells, tissues, and organs that work together to defend the body against harmful invaders such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. Without a functional immune system, even a minor infection could become life-threatening. The study of how the body mounts an immune response is central to biology, medicine, and public health, and it appears on virtually every major science exam from AP Biology to the MCAT and USMLE.

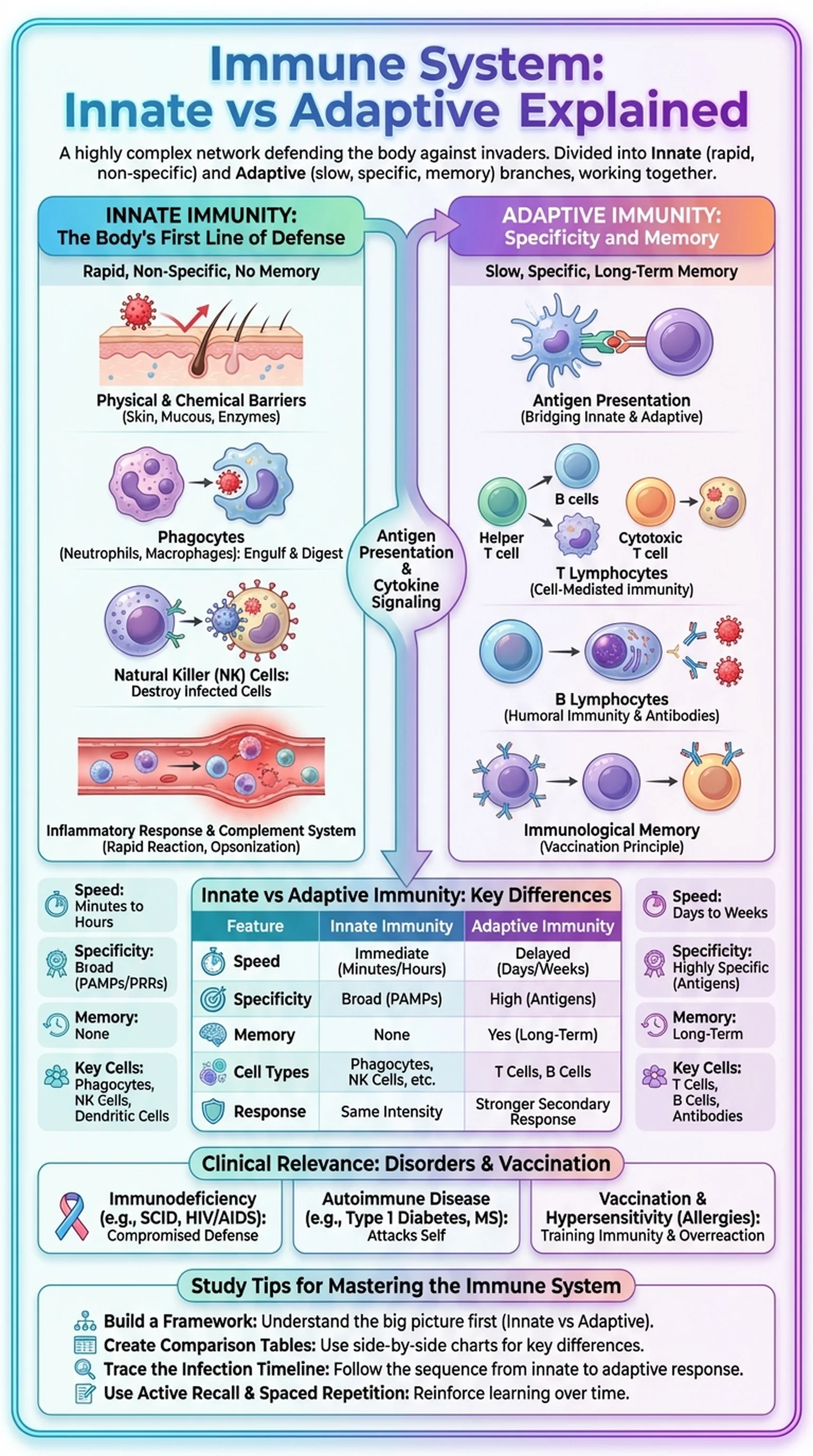

The immune system is broadly divided into two interconnected branches: innate immunity and adaptive immunity. Innate immunity provides the body's first line of defense and responds rapidly to a wide range of pathogens without prior exposure. Adaptive immunity, by contrast, develops more slowly but generates a highly specific immune response tailored to individual pathogens, complete with immunological memory that enables faster and stronger responses upon re-exposure. The concept of innate vs adaptive immunity is foundational to understanding how vaccines work, why transplant rejection occurs, and how autoimmune diseases develop.

These two branches do not operate in isolation. Innate immunity activates and instructs adaptive immunity through antigen presentation and cytokine signaling, while adaptive immune cells can enhance innate defenses through antibody-mediated opsonization and complement activation. Understanding the cooperation between innate and adaptive immunity is essential for appreciating the full sophistication of the immune response.

Key Terms

The collective network of cells, tissues, organs, and molecules that protects the body from infectious agents and abnormal cells.

The non-specific, rapidly acting branch of the immune system that provides immediate defense against pathogens without requiring prior exposure.

The antigen-specific branch of the immune system that develops over days, produces targeted responses, and generates immunological memory.

The coordinated reaction of the immune system to the detection of a pathogen or foreign substance, involving both innate and adaptive mechanisms.

Any molecule, typically a protein or polysaccharide, that can be recognized by the adaptive immune system and trigger an immune response.