What Is Integration by Parts?

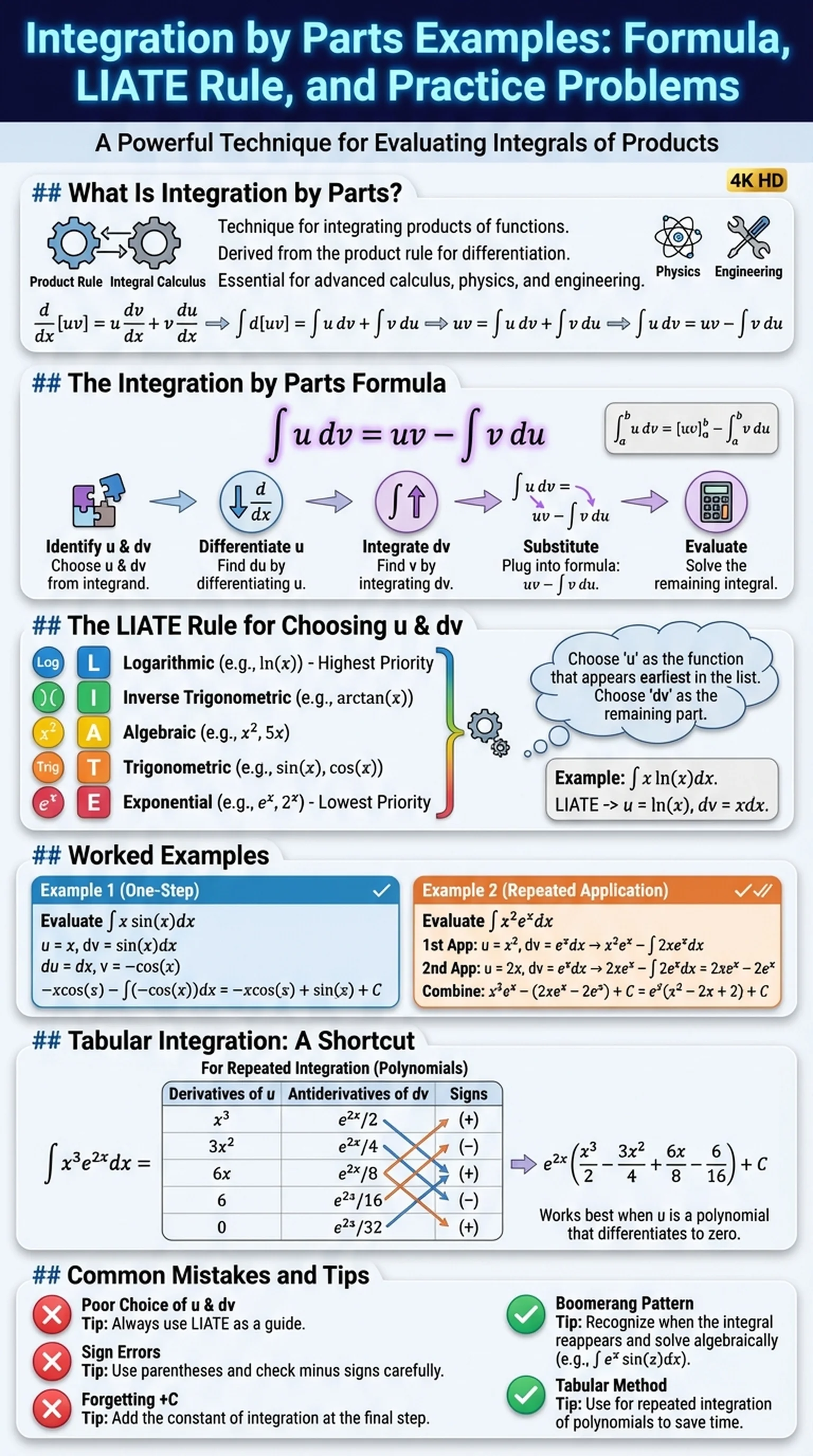

Integration by parts is one of the most important techniques in integral calculus, used to evaluate integrals of products of functions that cannot be solved by simple substitution or direct antidifferentiation. It is the integration counterpart of the product rule from differential calculus and is essential for any student studying calculus at the college level, preparing for the AP Calculus BC exam, or working through engineering mathematics courses.

The core idea behind integration by parts is to transform a difficult integral into a simpler one by strategically choosing which part of the integrand to differentiate and which part to integrate. When you encounter an ∫ of the form integral of f(x)g(x)dx that does not yield to u-substitution, integration by parts is typically the next technique to try. Common examples include integrals like ∫ of x*e^x dx, ∫ of x*sin(x) dx, and ∫ of ln(x) dx.

Historically, integration by parts derives from the product rule for differentiation. Since the derivative of a product u*v equals u*dv + v*du, integrating both sides and rearranging yields the integration by parts formula. This derivation is not just a mathematical curiosity — understanding it helps you see why the technique works and builds intuition for choosing u and dv effectively.

Integration by parts appears throughout mathematics, physics, and engineering. It is used to derive many important formulas, including reduction formulas for powers of trigonometric functions, the Laplace transform of derivatives, and solutions to differential equations. In probability and statistics, it appears in the derivation of expected values and moment-generating functions. Mastering integration by parts examples across these diverse applications is essential for building a deep and flexible understanding of integral calculus.

Key Terms

A technique for evaluating integrals of products of functions by transforming the integral using the formula: integral of u dv = uv - integral of v du.

The branch of calculus concerned with finding antiderivatives and evaluating definite and indefinite integrals.

The differentiation rule stating that d/dx[u*v] = u*dv/dx + v*du/dx, from which integration by parts is derived.

The process of finding a function whose derivative equals a given function, also known as finding the indefinite integral.

An integration technique that reverses the chain rule by substituting a new variable for part of the integrand.