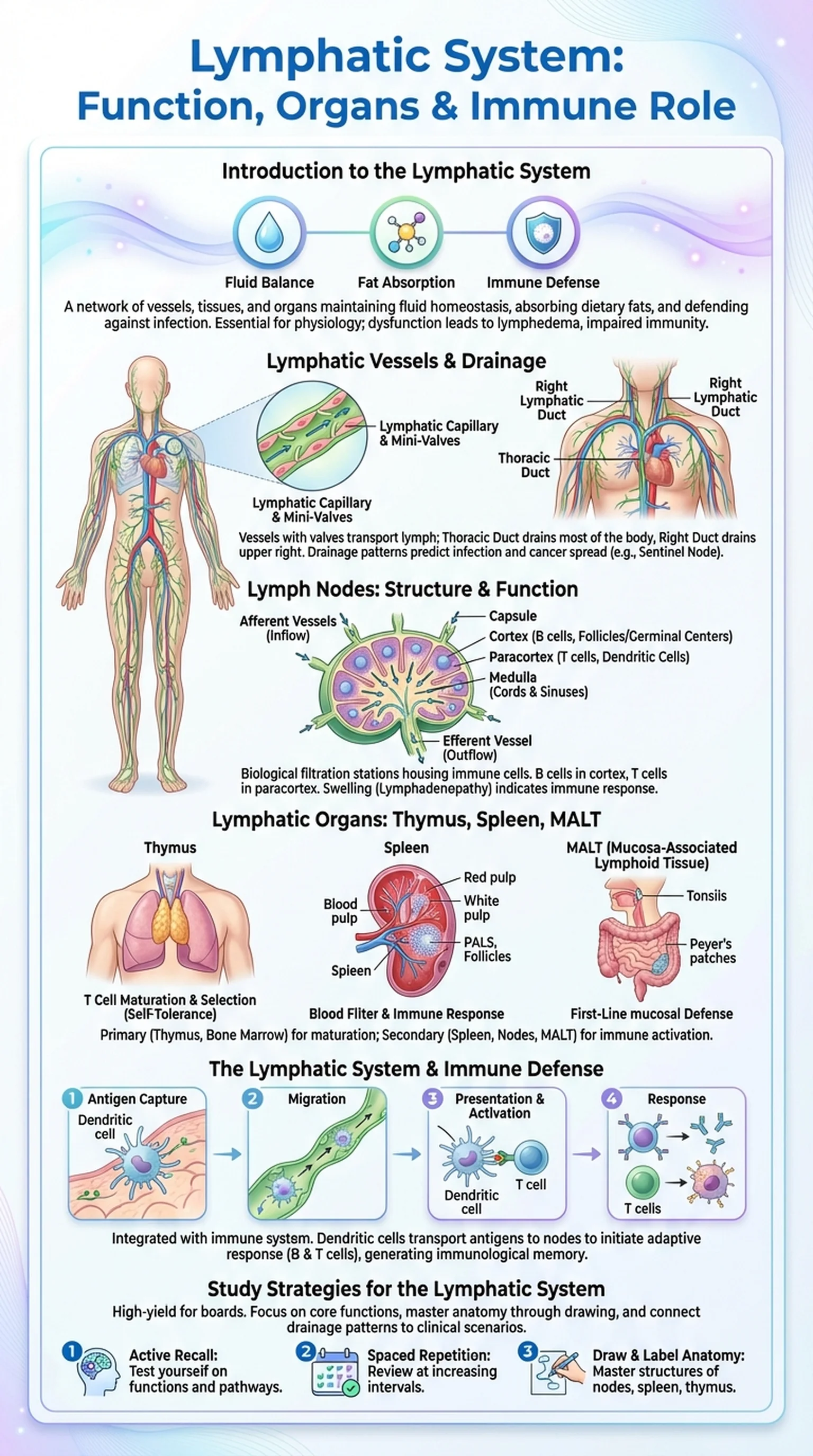

Introduction to the Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system is a network of vessels, tissues, and organs that works in close partnership with the cardiovascular and immune systems to maintain fluid homeostasis, absorb dietary fats, and defend the body against infection. Despite being less familiar to many students than the circulatory or respiratory systems, the lymphatic system plays an indispensable role in human physiology. Without a functioning lymphatic system, tissues would become waterlogged with interstitial fluid, dietary lipids could not be properly absorbed, and the body's immune surveillance would be critically impaired.

The lymphatic system can be understood as having three primary functions. First, lymphatic function in fluid balance involves the collection and return of excess interstitial fluid that leaks out of blood capillaries during normal circulation. This recovered fluid, once inside the lymphatic vessels, is called lymph. Approximately three liters of fluid are returned to the blood via the lymphatic system each day, preventing the accumulation of edema. Second, the lymphatic system serves as the primary route for absorbing long-chain fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamins from the small intestine through specialized lymphatic vessels called lacteals. Third, and perhaps most importantly, the lymphatic system is a central component of the adaptive and innate immune response, housing immune cells and providing the anatomical framework for immune surveillance and activation.

Understanding lymphatic function is essential for medical and anatomy students because dysfunction of this system underlies conditions ranging from lymphedema and infection to cancer metastasis. Lymphatic drainage patterns dictate how infections and malignancies spread through the body, making this knowledge directly applicable to clinical diagnosis and surgical planning.

Key Terms

A network of vessels, tissues, and organs that maintains fluid balance, absorbs dietary fats, and provides immune defense throughout the body.

The clear, protein-rich fluid collected from interstitial spaces by lymphatic vessels and returned to the blood circulation.

The combined roles of the lymphatic system in fluid recovery, fat absorption, and immune surveillance and response.

Specialized lymphatic capillaries in the villi of the small intestine that absorb dietary fats and transport them as chyle.