What Is Muscle Contraction?

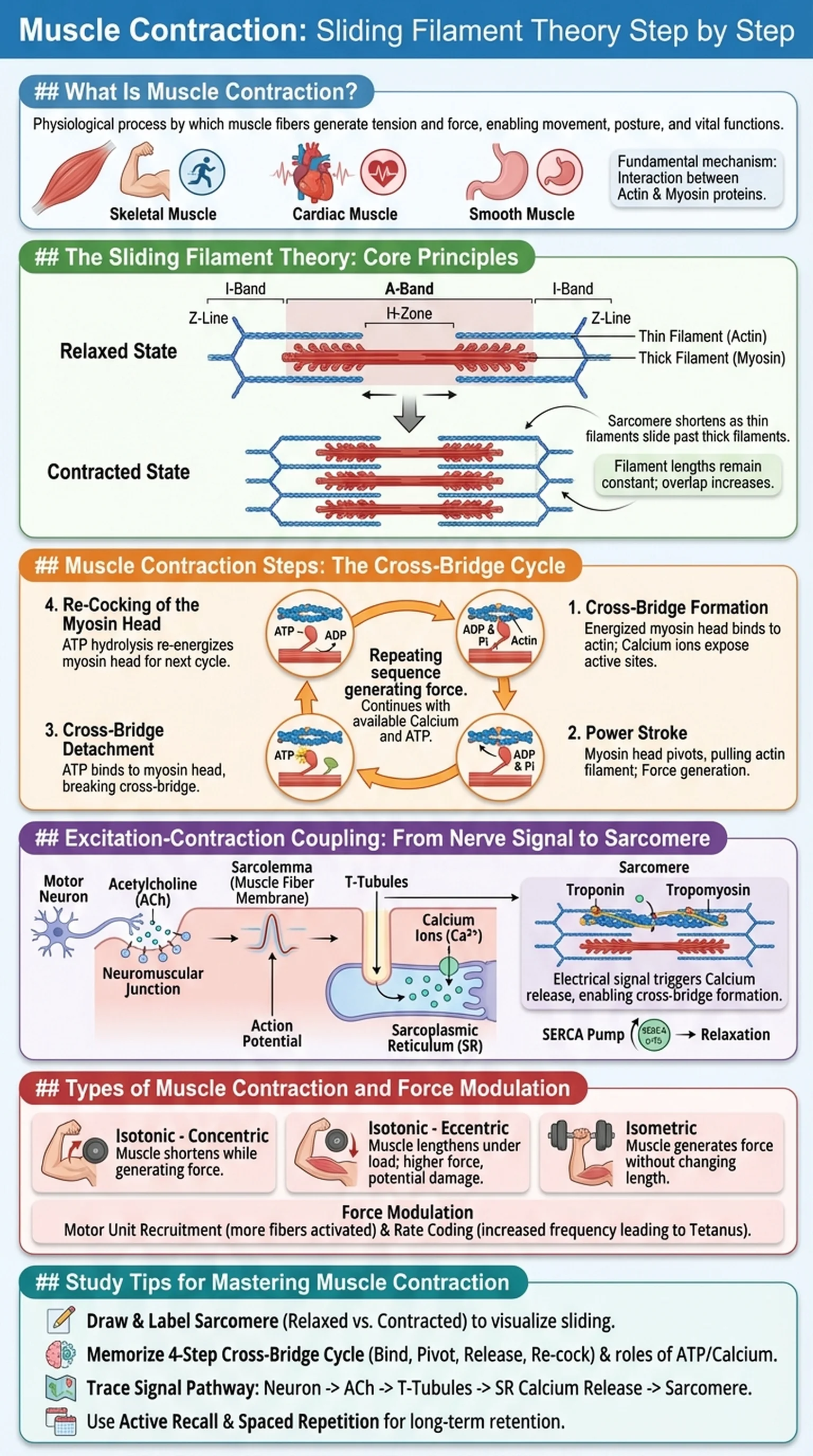

Muscle contraction is the physiological process by which muscle fibers generate tension and produce force, enabling movement, posture maintenance, and vital functions such as heartbeat and digestion. At the cellular level, muscle contraction involves the coordinated interaction of contractile proteins within specialized cells called muscle fibers, or myocytes. Whether you are lifting a weight, blinking an eye, or pumping blood through your circulatory system, muscle contraction is the fundamental mechanism at work.

There are three types of muscle tissue in the human body: skeletal, cardiac, and smooth. Skeletal muscle is under voluntary control and is responsible for locomotion and purposeful movements. Cardiac muscle contracts rhythmically to pump blood, and smooth muscle lines the walls of hollow organs and blood vessels, controlling involuntary functions like peristalsis. While the underlying molecular mechanism differs slightly among these types, the basic principle of muscle contraction remains rooted in the interaction between the proteins actin and myosin.

The study of muscle contraction is central to anatomy, physiology, kinesiology, and clinical medicine. Understanding the muscle contraction steps at the molecular level allows students to appreciate how defects in the contractile machinery lead to diseases such as muscular dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Furthermore, the concept of the sarcomere as the functional unit of contraction provides an elegant framework for understanding how microscopic protein movements translate into macroscopic force generation. In this article, we will explore the sliding filament theory in detail, walking through each step of the cross-bridge cycle and explaining how the sarcomere shortens to produce muscle contraction.

Key Terms

The physiological process by which muscle fibers generate tension through the interaction of contractile proteins, producing force and movement.

The basic functional and structural unit of skeletal and cardiac muscle, defined as the segment between two Z-lines.

A thin filament protein in the sarcomere that provides binding sites for myosin heads during muscle contraction.

A thick filament protein with globular heads that bind to actin and generate force through the power stroke during muscle contraction.