What Is Pharmacokinetics?

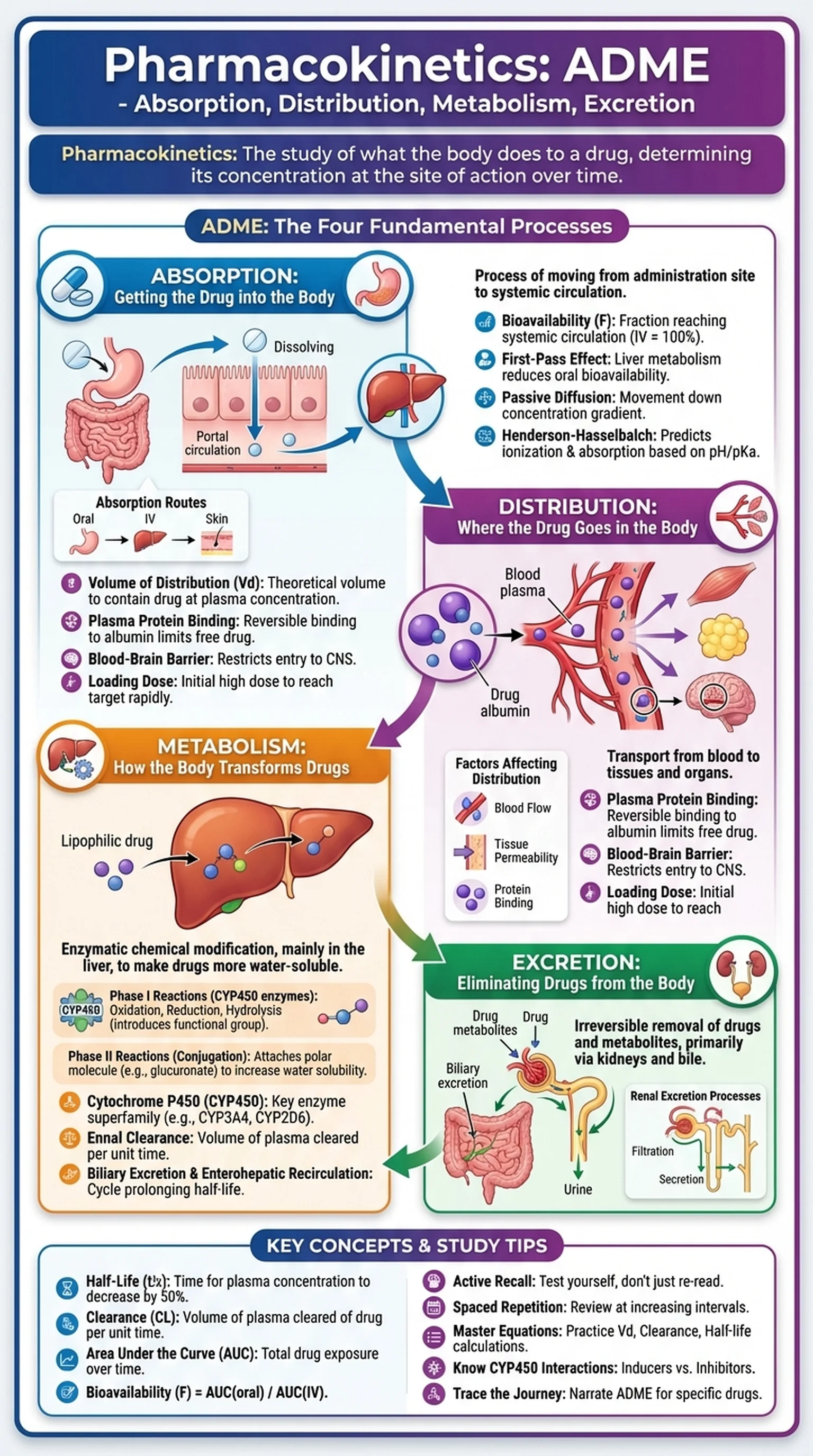

Pharmacokinetics is the branch of pharmacology that studies what the body does to a drug after it is administered. While pharmacodynamics asks how a drug affects the body, pharmacokinetics asks the complementary question: how does the body affect the drug? The field is organized around the acronym ADME, which stands for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion. These four processes determine the concentration of a drug at its site of action over time and therefore dictate the onset, intensity, and duration of a drug's therapeutic effect.

Understanding pharmacokinetics is essential for healthcare professionals because it provides the scientific basis for drug dosing, route of administration, dosing interval, and drug interactions. A drug that is poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract may require intravenous administration. A drug that is rapidly metabolized may need frequent dosing. A drug that accumulates in patients with renal impairment may require dose reduction to prevent toxicity. Each of these clinical decisions depends on pharmacokinetic principles.

Pharmacology students, medical students, and pharmacy students encounter pharmacokinetics as one of the most quantitative and clinically relevant subjects in their training. It appears heavily on licensing examinations including the USMLE, NAPLEX, and MCAT. The mathematical relationships that govern drug concentration over time, including concepts such as half-life, volume of distribution, clearance, and bioavailability, form the quantitative backbone of ADME and allow clinicians to predict how drugs will behave in individual patients with varying organ function, body composition, and genetic backgrounds.

Key Terms

The study of how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and excretes drugs over time, determining drug concentration at the site of action.

An acronym for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion, the four fundamental pharmacokinetic processes that determine a drug's fate in the body.

The time required for the plasma concentration of a drug to decrease by 50%, determined by the drug's volume of distribution and clearance.

The fraction of an administered drug dose that reaches the systemic circulation in an unchanged, active form.

The volume of plasma from which a drug is completely removed per unit time, reflecting the body's efficiency at eliminating the drug.