What Is Pharmacodynamics?

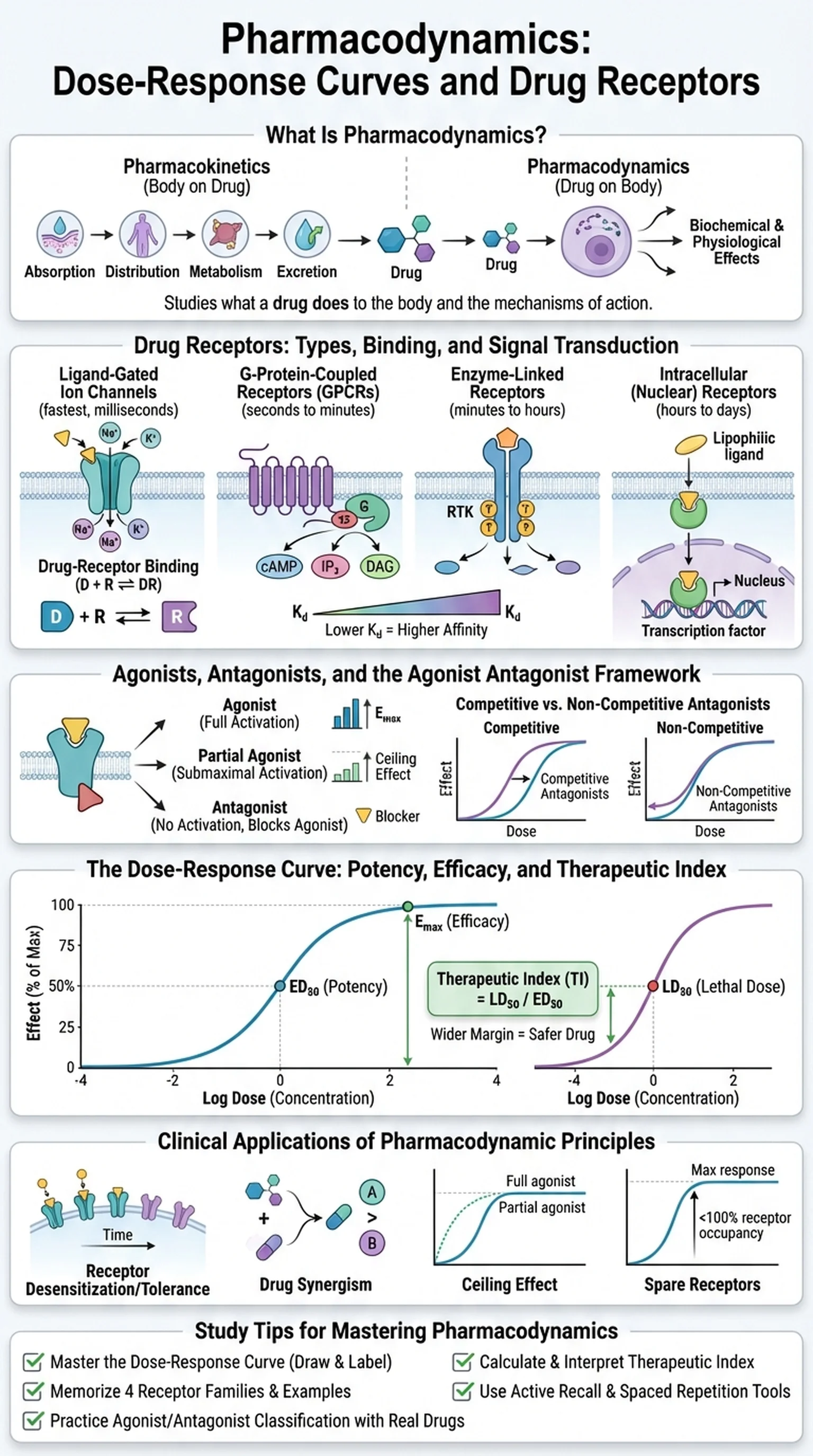

Pharmacodynamics is the branch of pharmacology that studies what a drug does to the body. While pharmacokinetics describes the body's effects on a drug (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion), pharmacodynamics examines the biochemical and physiological effects that drugs produce and the mechanisms by which they produce them. At its core, pharmacodynamics seeks to answer the question: how does a drug, once it reaches its target, alter cellular and organ function to produce a therapeutic or toxic effect?

The foundation of pharmacodynamics rests on the concept of drug receptors. The vast majority of drugs exert their effects by interacting with specific macromolecular targets in the body, most commonly proteins. These targets include cell-surface receptors (such as G-protein-coupled receptors, ligand-gated ion channels, and receptor tyrosine kinases), intracellular receptors (such as nuclear hormone receptors), enzymes, ion channels, and transporter proteins. The binding of a drug to its receptor initiates a cascade of molecular events that ultimately produces the observed pharmacological effect.

Understanding pharmacodynamics is essential for students of medicine, pharmacy, and biomedical sciences because it provides the rationale for drug selection, explains why drugs have side effects, and predicts how drugs will interact when used in combination. Pharmacodynamics is heavily tested on licensing examinations including the USMLE, NAPLEX, and MCAT. The quantitative tools of pharmacodynamics, particularly the dose-response curve, allow clinicians and researchers to compare drug potency, efficacy, and safety in a rigorous, systematic manner that guides evidence-based prescribing.

Key Terms

The branch of pharmacology studying the biochemical and physiological effects of drugs on the body and their mechanisms of action.

Specific macromolecular targets (usually proteins) on or within cells to which drugs bind to produce their pharmacological effects.

The largest family of cell-surface receptors, consisting of seven transmembrane domains that activate intracellular G-proteins upon ligand binding.

The specific biochemical interaction through which a drug produces its pharmacological effect, typically involving binding to a receptor or enzyme.