Overview of Spinal Cord Anatomy

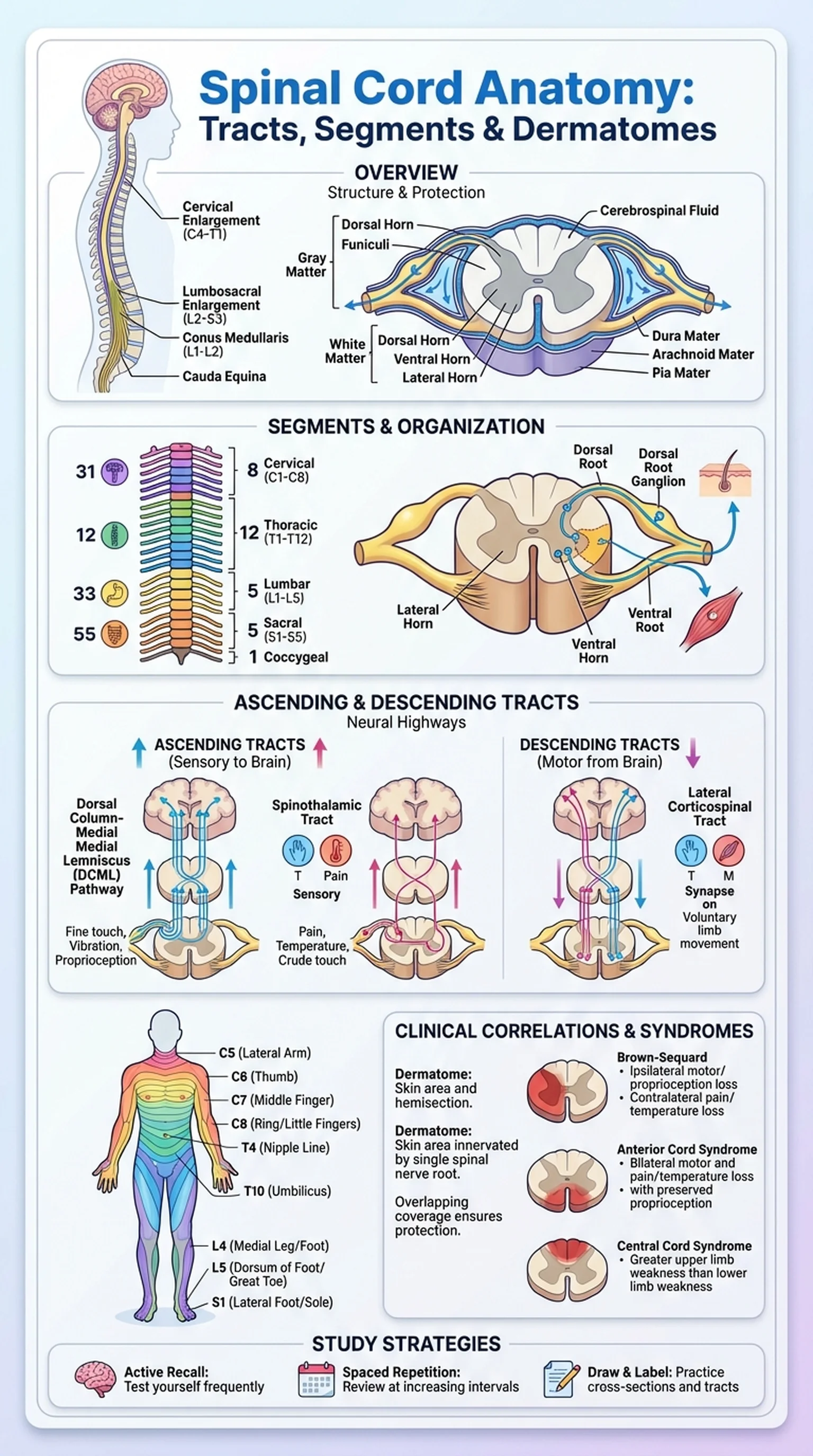

Spinal cord anatomy is one of the most clinically relevant topics in the study of the human nervous system. The spinal cord is a long, cylindrical structure of nervous tissue that extends from the brainstem at the foramen magnum to approximately the level of the first or second lumbar vertebra (L1-L2), where it terminates as the conus medullaris. Below this point, the spinal nerves continue as a bundle called the cauda equina. Understanding spinal cord anatomy is essential for diagnosing and localizing neurological injuries, interpreting imaging studies, and predicting functional deficits after trauma.

The spinal cord is protected by the vertebral column and surrounded by three meningeal layers: the dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater. Cerebrospinal fluid circulates in the subarachnoid space, providing cushioning and metabolic support. In cross-section, the spinal cord reveals a butterfly-shaped core of gray matter surrounded by white matter. The gray matter contains neuronal cell bodies, interneurons, and synapses, while the white matter is composed of myelinated axon bundles organized into spinal cord tracts that carry information up and down the cord.

Two prominent enlargements are visible along the cord: the cervical enlargement (C4-T1) and the lumbosacral enlargement (L2-S3). These regions contain a greater concentration of motor neurons because they innervate the upper and lower limbs, respectively. The organization of spinal cord anatomy into discrete segments, each giving rise to a pair of spinal nerves, provides the structural basis for dermatomes and the clinical localization of spinal cord lesions.

Key Terms

A cylindrical structure of nervous tissue extending from the brainstem to the conus medullaris, serving as the main conduit for sensory and motor information between the brain and the body.

The tapered, terminal end of the spinal cord, typically located at the L1-L2 vertebral level in adults.

A bundle of spinal nerve roots descending below the conus medullaris within the vertebral canal, resembling a horse's tail.

The central butterfly-shaped region of the spinal cord containing neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, and synapses.

The outer region of the spinal cord composed of myelinated axon bundles (tracts) that transmit signals along the length of the cord.