Introduction to Joint Classification

Joints, also known as articulations, are the points where two or more bones meet in the body. Understanding the types of joints is fundamental to the study of human anatomy because joints determine the range and type of movement possible at each skeletal connection. Joint classification provides a systematic framework for organizing the hundreds of articulations in the human body according to their structural characteristics and functional capabilities. Without joints, the rigid skeleton would be incapable of the fluid, coordinated movements that define human locomotion, manual dexterity, and postural control.

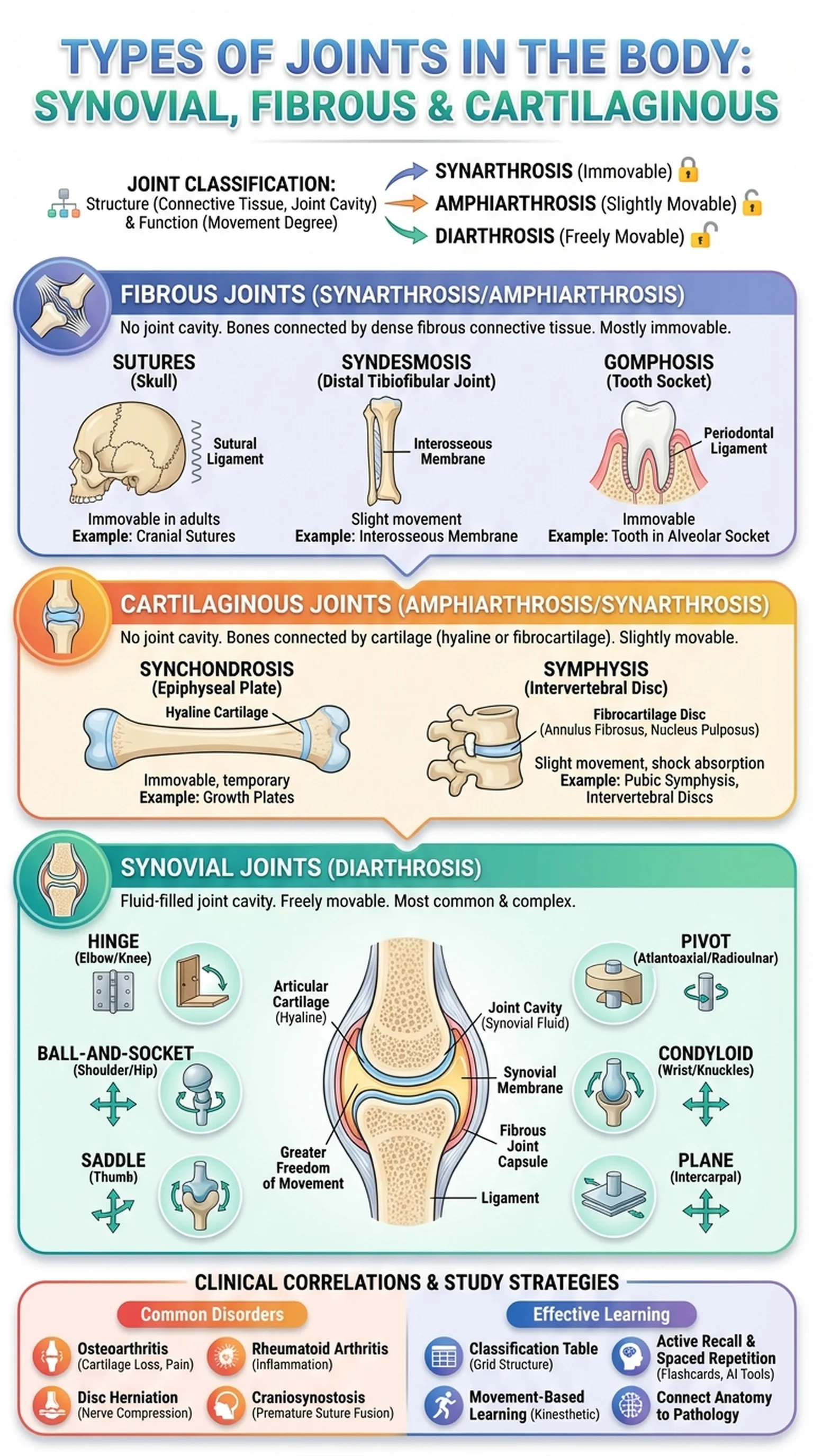

Joint classification can be approached from two complementary perspectives: structural and functional. Structural classification groups joints by the type of connective tissue that binds the bones together and whether a joint cavity is present. The three structural categories are fibrous joints (connected by dense fibrous tissue, no joint cavity), cartilaginous joints (connected by cartilage, no joint cavity), and synovial joints (separated by a fluid-filled joint cavity lined with synovial membrane). Functional classification groups joints by their degree of movement: synarthroses are immovable joints, amphiarthroses are slightly movable joints, and diarthroses are freely movable joints.

These two classification systems overlap in predictable ways. Most fibrous joints are synarthroses, most cartilaginous joints are amphiarthroses, and all synovial joints are diarthroses. Learning both systems simultaneously provides a more complete understanding of the types of joints and their clinical relevance. For students preparing for anatomy exams and board certifications, joint classification is a recurring theme that integrates concepts from musculoskeletal anatomy, kinesiology, and orthopedic medicine.

Key Terms

The classification of skeletal articulations based on structural composition (fibrous, cartilaginous, synovial) and functional mobility (synarthrosis, amphiarthrosis, diarthrosis).

The systematic categorization of joints by structure (type of connective tissue and presence of a joint cavity) and function (degree of permitted movement).

The point of contact between two or more bones, also known as a joint, which may allow varying degrees of movement.

An immovable joint, such as the sutures of the skull, where bones are tightly bound and no movement occurs.