What Are Mutations in Biology?

In mutation biology, a mutation is defined as any permanent change in the nucleotide sequence of an organism's DNA. Mutations are the ultimate source of all genetic variation, providing the raw material upon which natural selection and evolution act. Without mutations, populations would lack the genetic diversity needed to adapt to changing environments. However, most mutations are neutral or harmful, and only a small fraction confer a selective advantage.

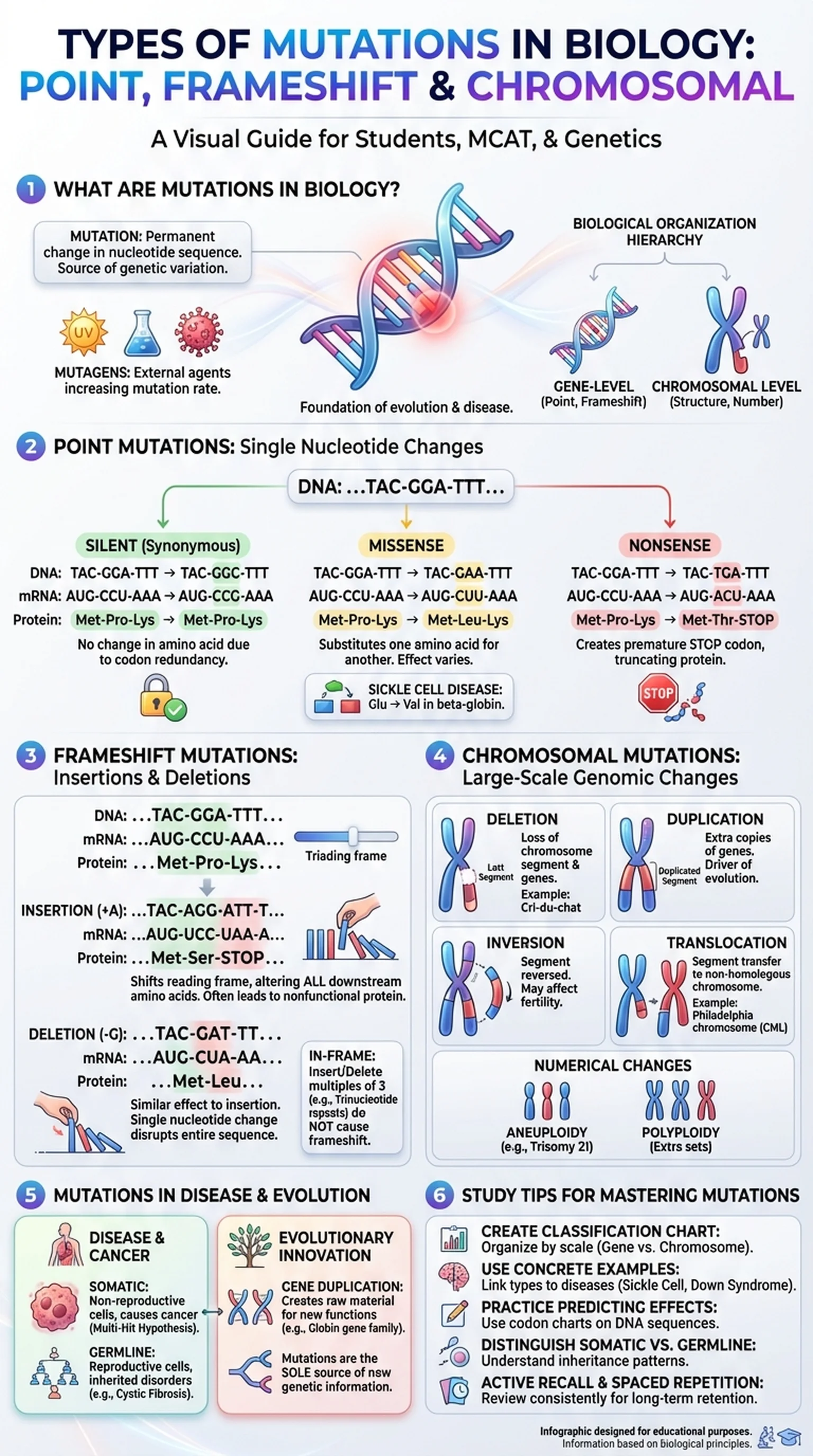

The types of mutations can be classified at multiple levels of biological organization. At the smallest scale, changes affecting one or a few nucleotides are called gene-level mutations, which include point mutations and frameshift mutations. At the largest scale, changes affecting the structure or number of entire chromosomes are called chromosomal mutations. Understanding this hierarchy is essential for studying genetics, molecular biology, and medicine, since different types of mutations produce vastly different effects on an organism's phenotype.

Mutations can arise spontaneously during DNA replication when the cell's proofreading machinery fails to correct an error, or they can be induced by external agents called mutagens. Chemical mutagens, such as benzene and nitrous acid, alter the chemical structure of DNA bases. Physical mutagens, such as ultraviolet light and ionizing radiation, cause direct damage to the DNA backbone or promote the formation of abnormal base pairs. Biological mutagens, including certain viruses and transposable elements, can insert foreign DNA sequences into the genome. Regardless of their origin, mutations are the foundation of mutation biology and a core concept in every genetics course.

Key Terms

A permanent change in the nucleotide sequence of DNA that may affect gene function and be passed to offspring.

An external agent (chemical, physical, or biological) that increases the rate of mutation in DNA.

The classification of mutations based on scale and mechanism, including point mutations, frameshift mutations, and chromosomal mutations.

Differences in DNA sequences among individuals in a population, ultimately generated by mutations.