Introduction to Antibiotic Classes

Antibiotic classes represent groups of antimicrobial agents that share similar chemical structures, mechanisms of action, and spectra of activity against bacteria. Since the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1928, the development of antibiotics has transformed medicine by enabling the treatment of previously fatal bacterial infections. Understanding the major antibiotic classes is essential for selecting appropriate therapy, minimizing adverse effects, and combating the growing threat of antibiotic resistance.

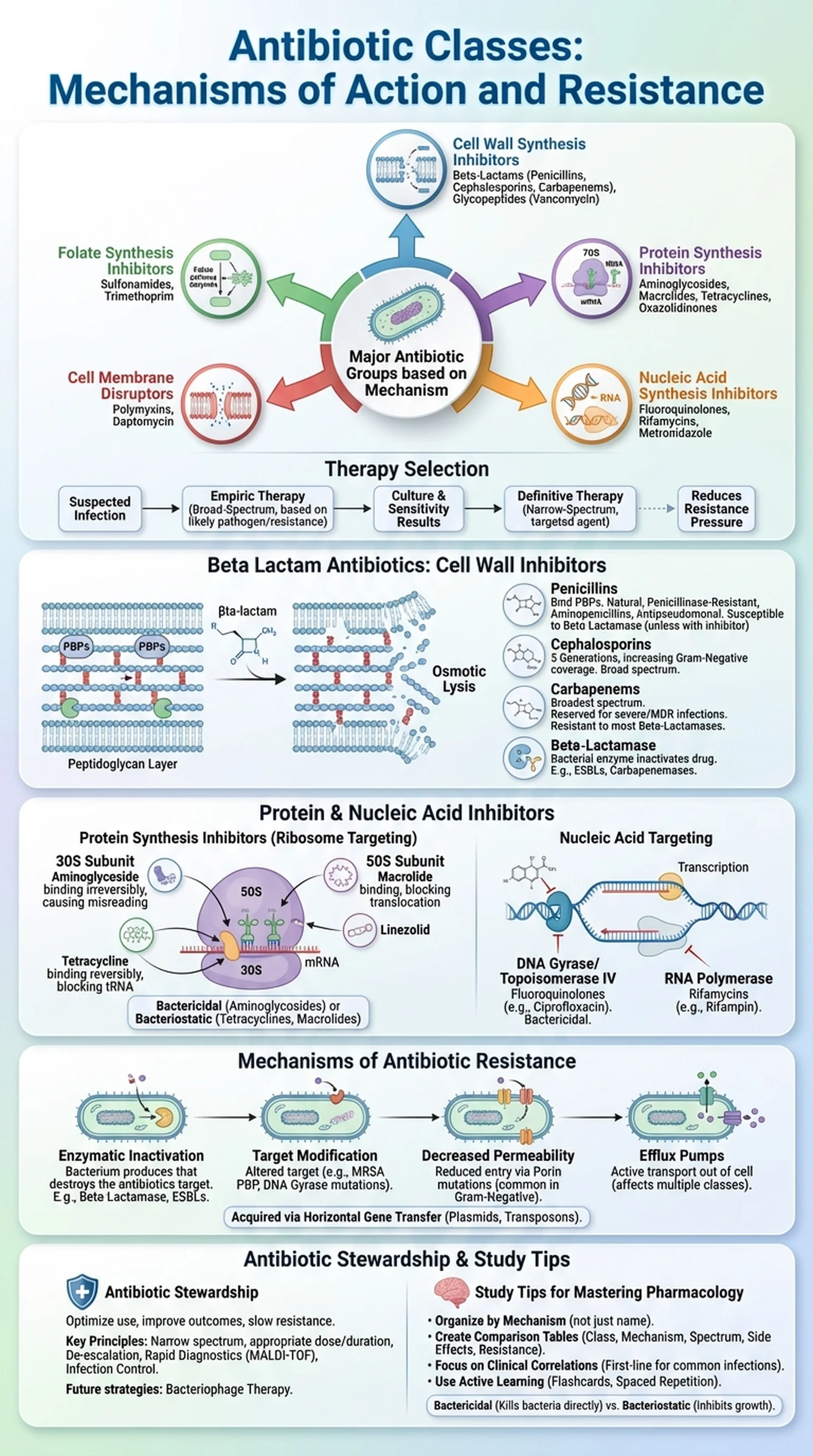

Antibiotics can be broadly categorized based on their mechanism of action into five major groups: cell wall synthesis inhibitors, protein synthesis inhibitors, nucleic acid synthesis inhibitors, folate synthesis inhibitors, and cell membrane disruptors. Each group contains multiple antibiotic classes with distinct chemical properties, pharmacokinetic profiles, and clinical indications. For example, cell wall synthesis inhibitors include the beta lactam antibiotics, glycopeptides, and fosfomycin, while protein synthesis inhibitors encompass aminoglycosides, macrolides, tetracyclines, and oxazolidinones.

The selection of an antibiotic depends on several factors, including the identity and susceptibility of the pathogen, the site of infection, the patient's allergies and comorbidities, and the local patterns of antibiotic resistance. Empiric therapy, initiated before culture results are available, relies on knowledge of which antibiotic classes are most likely to be effective against the suspected organisms. Definitive therapy, guided by culture and sensitivity data, allows clinicians to narrow the spectrum and choose the most targeted agent, thereby reducing selective pressure for antibiotic resistance.

Key Terms

Groups of antibiotics that share similar chemical structures and mechanisms of action, such as beta-lactams, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones.

The specific biochemical pathway or target through which an antibiotic exerts its antibacterial effect.

The range of bacterial species against which an antibiotic is effective, classified as narrow-spectrum or broad-spectrum.

Antibiotic treatment initiated before pathogen identification, based on the most likely causative organisms and local resistance patterns.