What Is Mendelian Genetics?

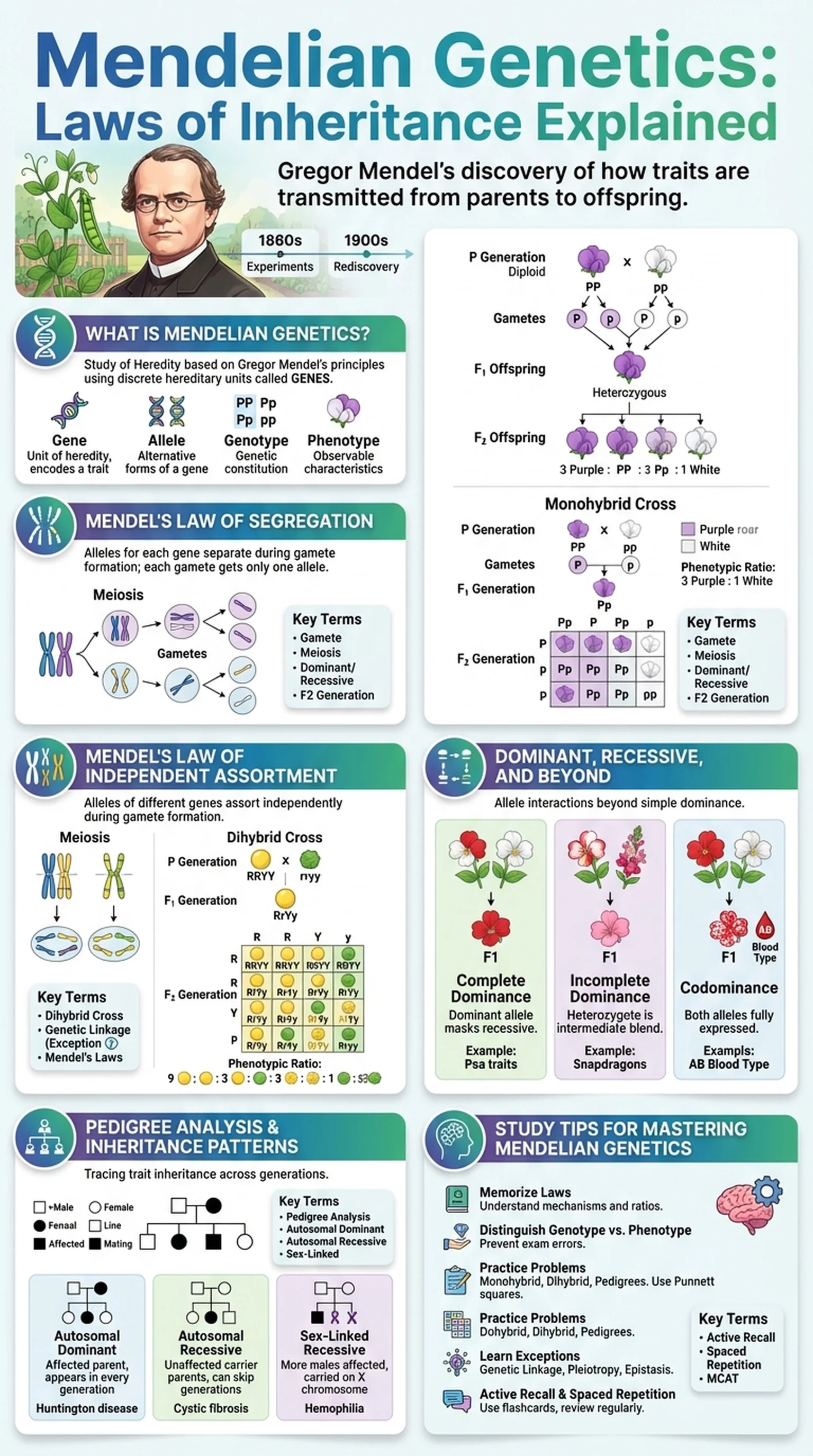

Mendelian genetics is the branch of biology that studies how traits are transmitted from parents to offspring according to the principles first discovered by Gregor Mendel in the 1860s. Mendel, an Augustinian friar and scientist, conducted systematic breeding experiments with pea plants (Pisum sativum) in the monastery garden at Brno, in what is now the Czech Republic. Through meticulous observation and quantitative analysis, he identified fundamental patterns of inheritance that would later form the foundation of modern genetics.

Mendelian genetics centers on the concept that traits are determined by discrete hereditary units, which we now call genes. Each organism inherits two copies of each gene, one from each parent. These alternative forms of a gene are known as alleles. When both alleles are the same, the organism is homozygous for that trait; when the alleles differ, the organism is heterozygous. The specific combination of alleles an organism carries constitutes its genotype, while the observable expression of those alleles constitutes its phenotype. The distinction between genotype and phenotype is one of the most important concepts in Mendelian genetics.

Mendel's work was remarkable not only for its experimental rigor but also for its use of mathematical ratios to describe inheritance patterns. He published his findings in 1866, but his work was largely ignored until 1900, when three scientists independently rediscovered his principles. Today, Mendelian genetics provides the conceptual framework for understanding the laws of inheritance, dominant recessive relationships, and the prediction of offspring traits using tools like the Punnett square.

Key Terms

The study of heredity based on the principles discovered by Gregor Mendel, focusing on how traits are passed from parents to offspring through discrete hereditary units.

A unit of heredity that occupies a specific position (locus) on a chromosome and encodes a particular trait.

The genetic constitution of an organism, represented by the alleles it carries for one or more genes.

The observable physical, biochemical, or behavioral characteristics of an organism resulting from the expression of its genotype.