Introduction to Neuroanatomy and Brain Organization

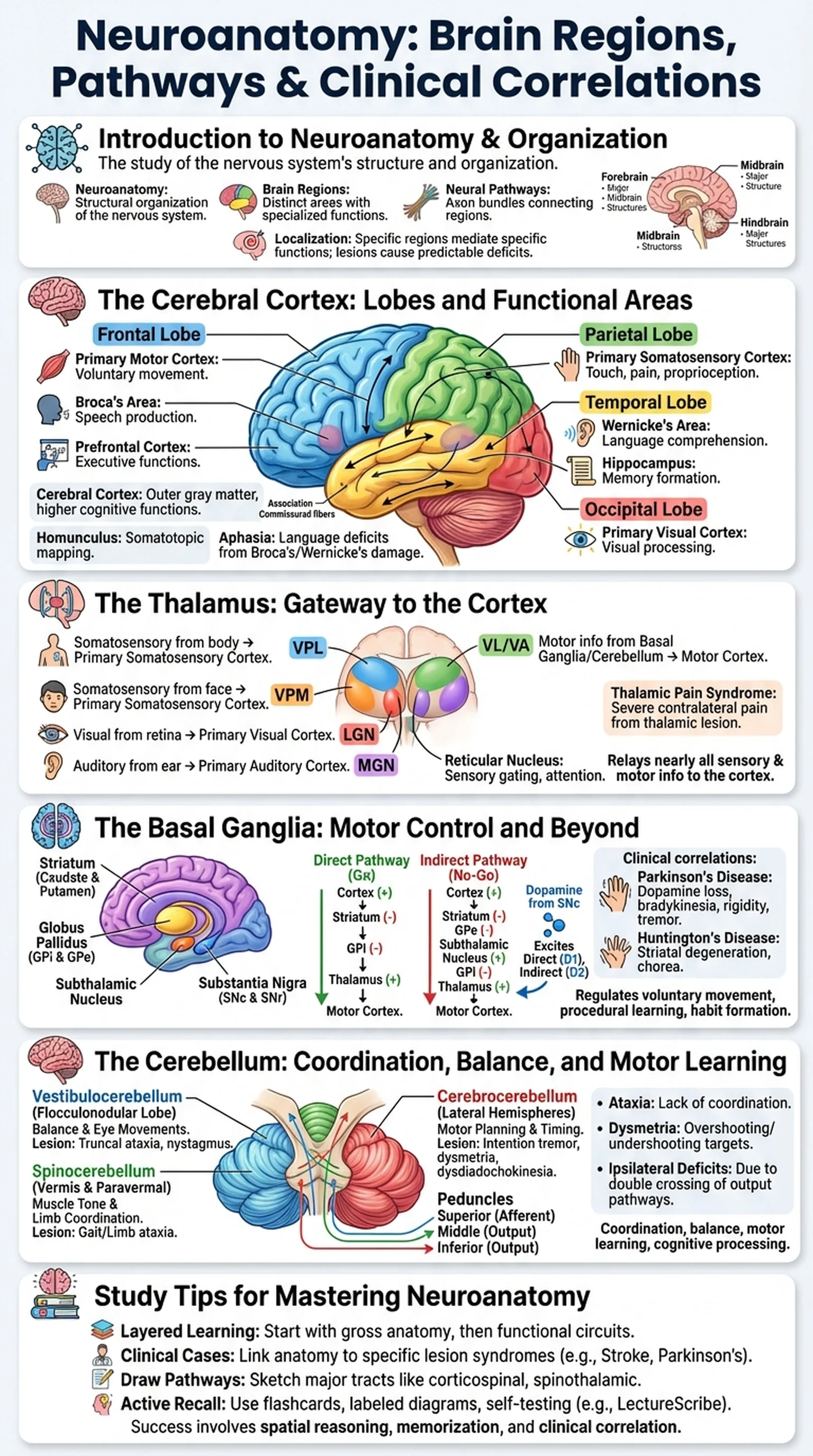

Neuroanatomy is the branch of anatomy dedicated to the study of the structure and organization of the nervous system. For medical students, neuroscience majors, and allied health professionals, a solid understanding of neuroanatomy provides the essential framework for interpreting clinical findings, localizing lesions, and understanding the neural basis of behavior. The human brain contains approximately 86 billion neurons organized into distinct brain regions, each with specialized functions and interconnected by elaborate neural pathways.

The brain can be divided into several major structures based on embryological development. The forebrain (prosencephalon) gives rise to the cerebral cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus, and basal ganglia. The midbrain (mesencephalon) contains structures involved in visual and auditory reflexes, motor control, and arousal. The hindbrain (rhombencephalon) comprises the pons, medulla oblongata, and cerebellum. Each of these brain regions contributes uniquely to the integrated functioning of the nervous system.

Understanding neuroanatomy requires learning both structure and connectivity. Individual brain regions do not operate in isolation; instead, they communicate through bundles of axons called neural pathways or tracts. These pathways can be ascending (carrying sensory information to the cortex), descending (carrying motor commands from the cortex to the spinal cord), or associative (connecting different cortical areas within the same hemisphere). The clinical relevance of neuroanatomy lies in the principle of localization: specific lesions in specific brain regions produce predictable clinical deficits. This principle allows clinicians to pinpoint the location of strokes, tumors, and degenerative diseases based on a patient's neurological examination.

Key Terms

The study of the structural organization of the nervous system, including the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves.

Anatomically and functionally distinct areas of the brain, including the cerebral cortex, thalamus, basal ganglia, cerebellum, brainstem, and others.

Bundles of axons connecting different brain regions, transmitting sensory, motor, and associative information throughout the nervous system.

The neurological principle that specific brain regions mediate specific functions, allowing clinicians to identify lesion sites from clinical symptoms.